Reach Out and Touch Faith

Originally published on Lapham's Quarterly Roundtable.

Traffic lights dot the streets of Naples like rhinestones. I’m not being romantic—I mean they’re shiny and worthless. Locals telegraph their unwillingness to stop on red with the internationally understood middle finger, which means tourists like me learn quickly that Neapolitan traffic isn’t ruled by lights or laws. It obeys the sea of motorbikes. Cars go when they go and stop to avoid vehicular manslaughter. Renting a car here wasn’t sensible, but it was the only way I could get to Bonito, where I had made an appointment to meet its most powerful and reclusive resident: a naked mummy named Zio Vincenzo Camuso, or, in English, Uncle Vincent.

Bonito is tiny. It’s not much more than twelve streets on top of a hill surrounded by Campania’s farmland. As soon as I turn off the dirt road onto the city’s cobblestones, a sign with a cross and arrow points me not in the direction of the parish church but toward Uncle Vincent’s shrine, a yellow stucco building that’s a little too big to be a mausoleum and a little too small to be an apartment. I borrow the key to the shrine from city hall and park across the street. I watch as two men in a garbage truck drive by: one makes the sign of the cross and the other tips his hat to the shrine’s iron door.

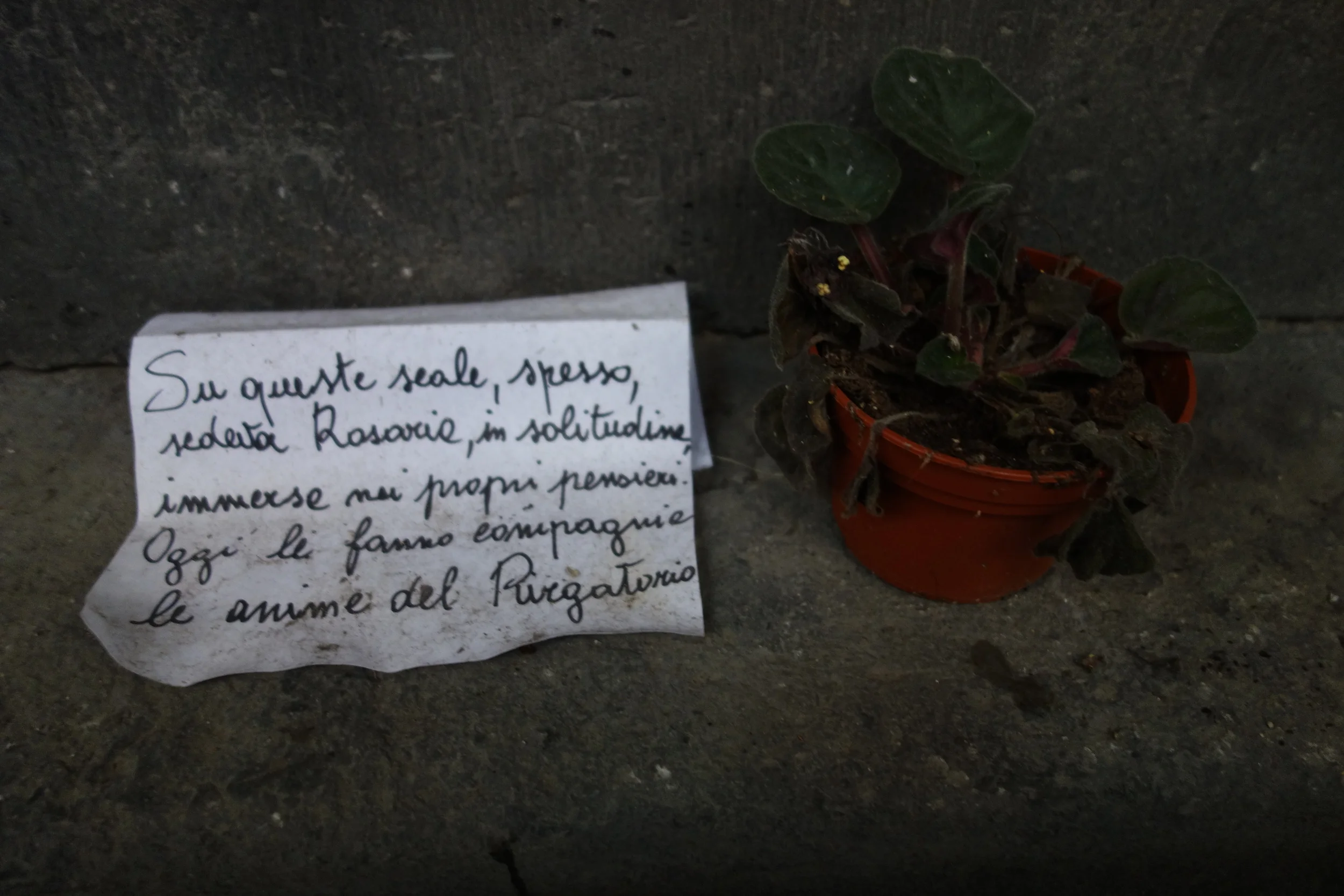

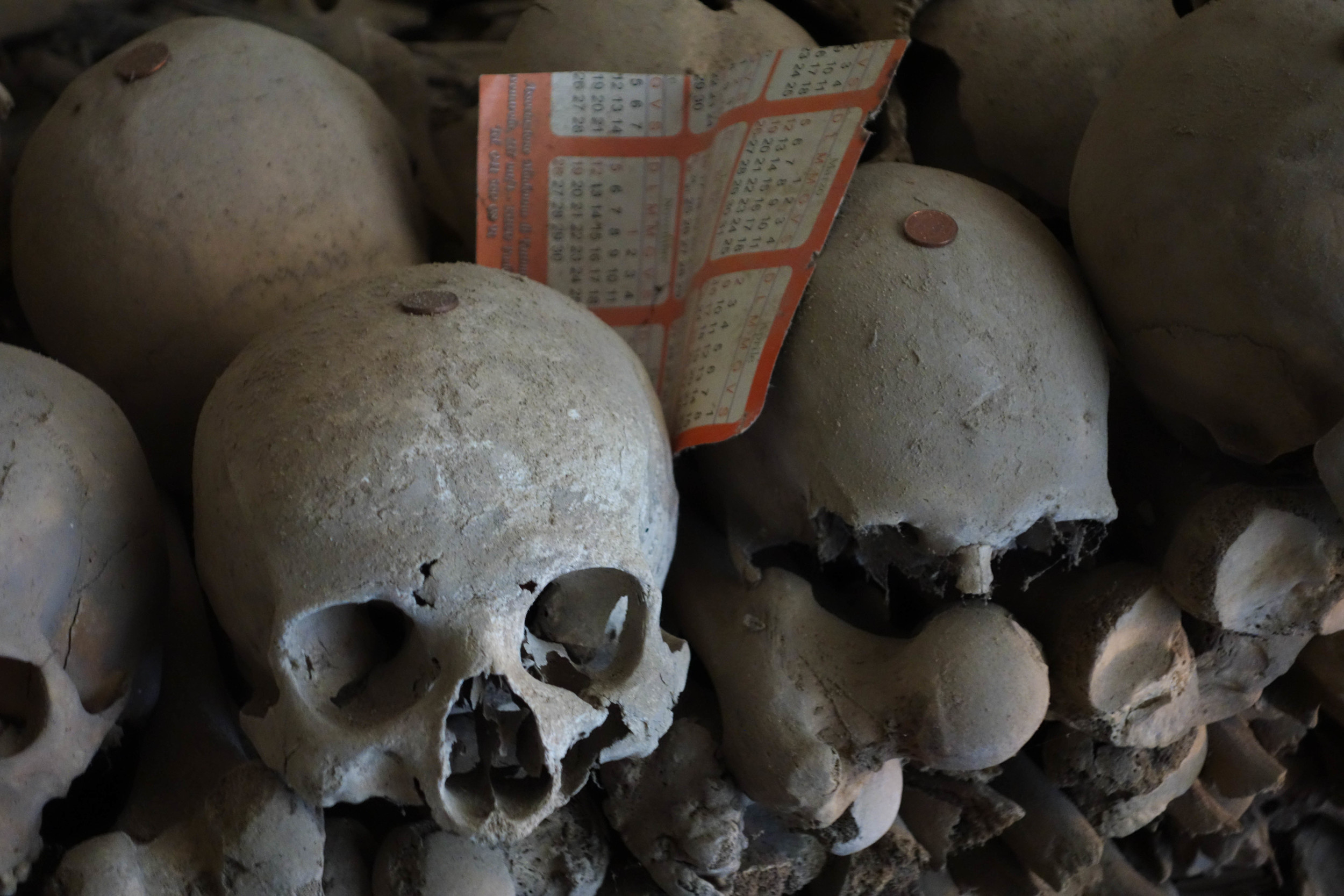

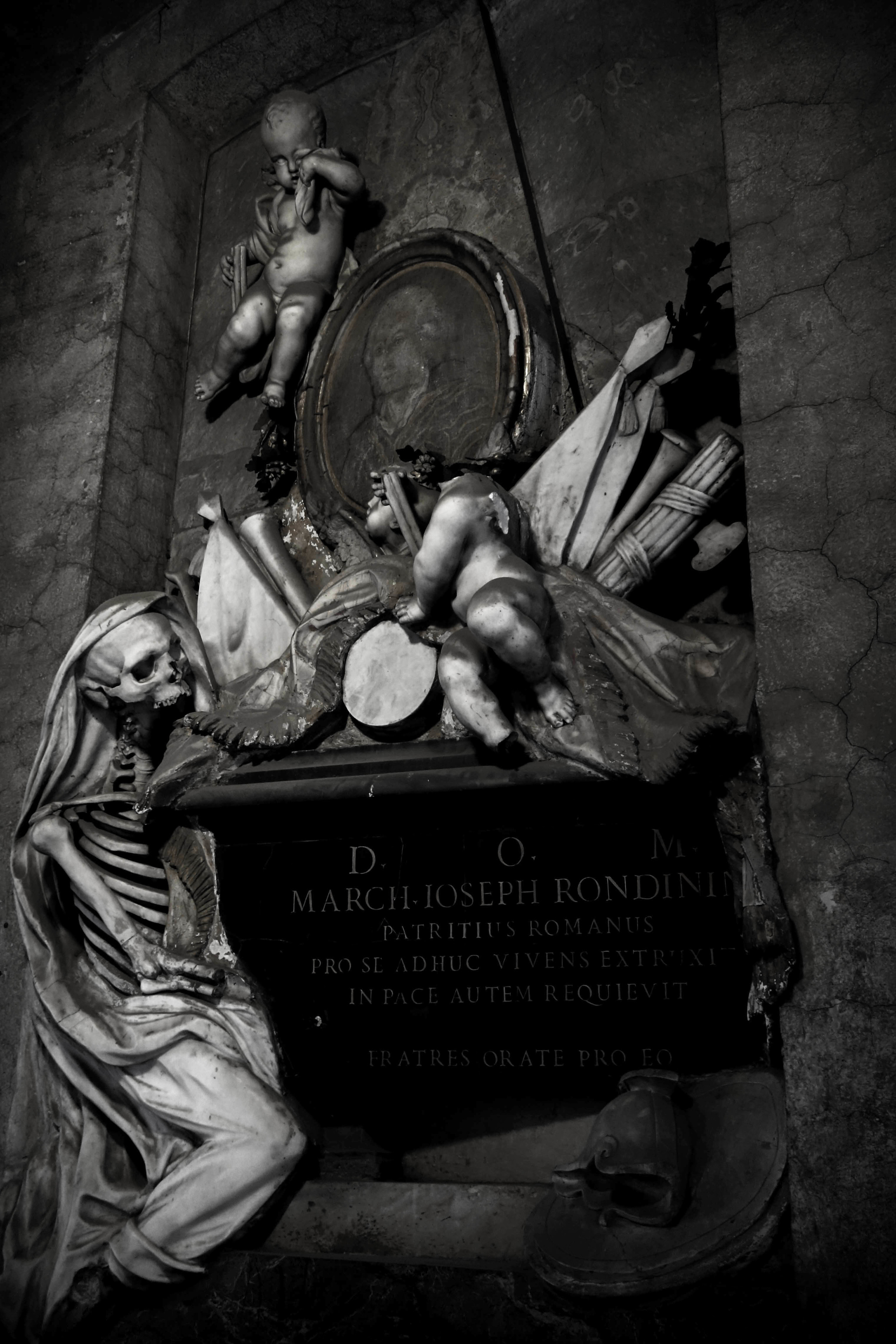

As soon as I’m inside, the reason for their reverence is clear. Uncle Vincent is known for granting miracles. Photos and gifts from grateful recipients are stuck to every wall and stacked in every corner. There are rosaries, electric candles, potted plants, and ribbons, and baby clothes and thank-you notes from women who asked for help in childbirth. There are hundreds of flat metal charms called ex votos left by people whose prayers to Uncle Vincent have been answered. Sometimes the charms represent the thing they asked for—a baby or a computer—but mostly they depict body parts that have been healed. On one wall a copper leg is pinned to a corkboard next to a picture of a smiling man with his leg in a cast. There are metal eyes, breasts, hands, guts, hearts (both the sacred and the anatomical variety), and even a paunchy belly. A photocopied page of local lore at the shrine describes how hands-on Uncle Vincent can be when he grants these medical miracles. Some people believe he operates on his devotees in their sleep, leaving them cured but with a telltale scar to prove that the work’s been done.

Ex votos, photograph, and notes at the shrine of Uncle Vincent. Photograph by Elizabeth Harper.

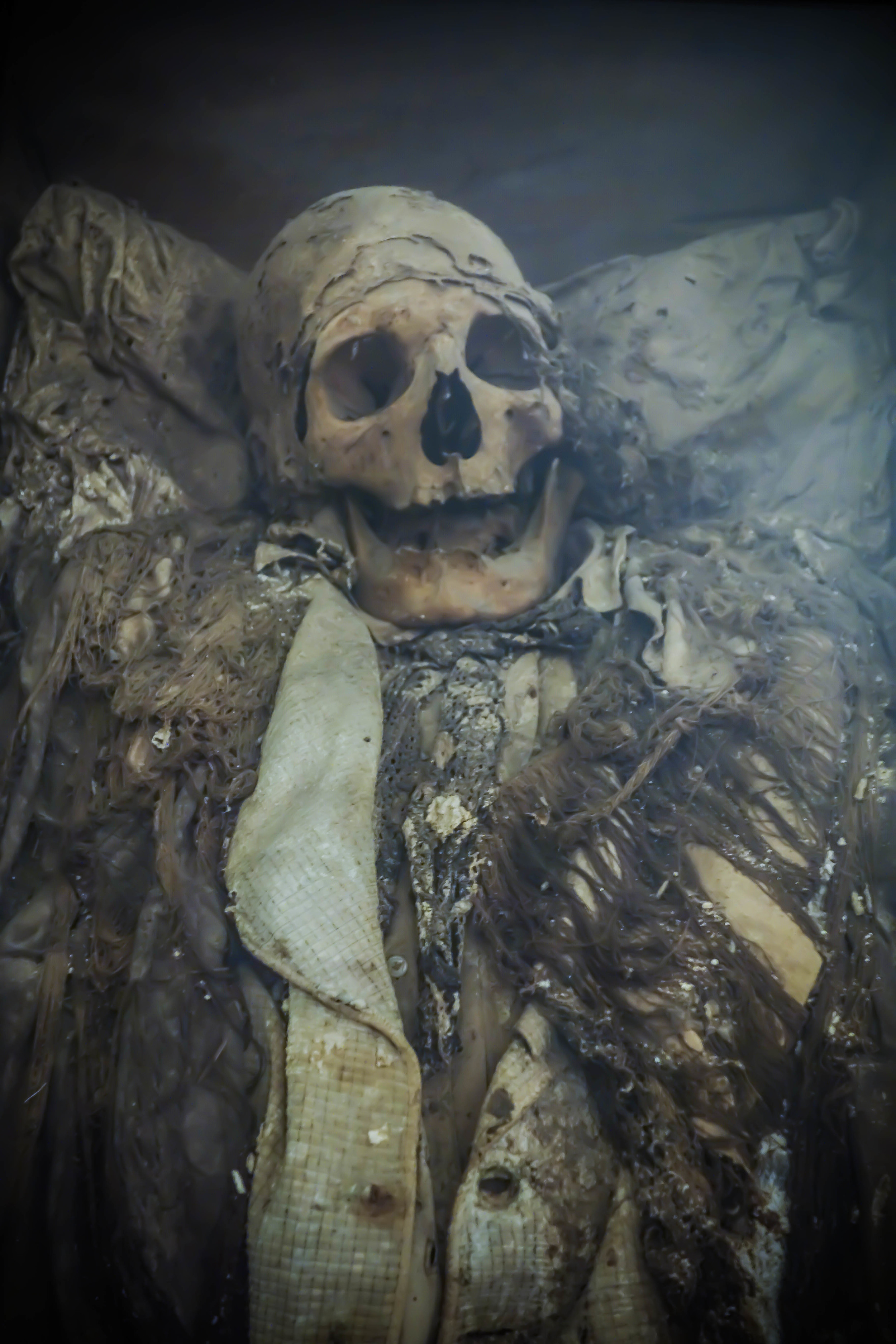

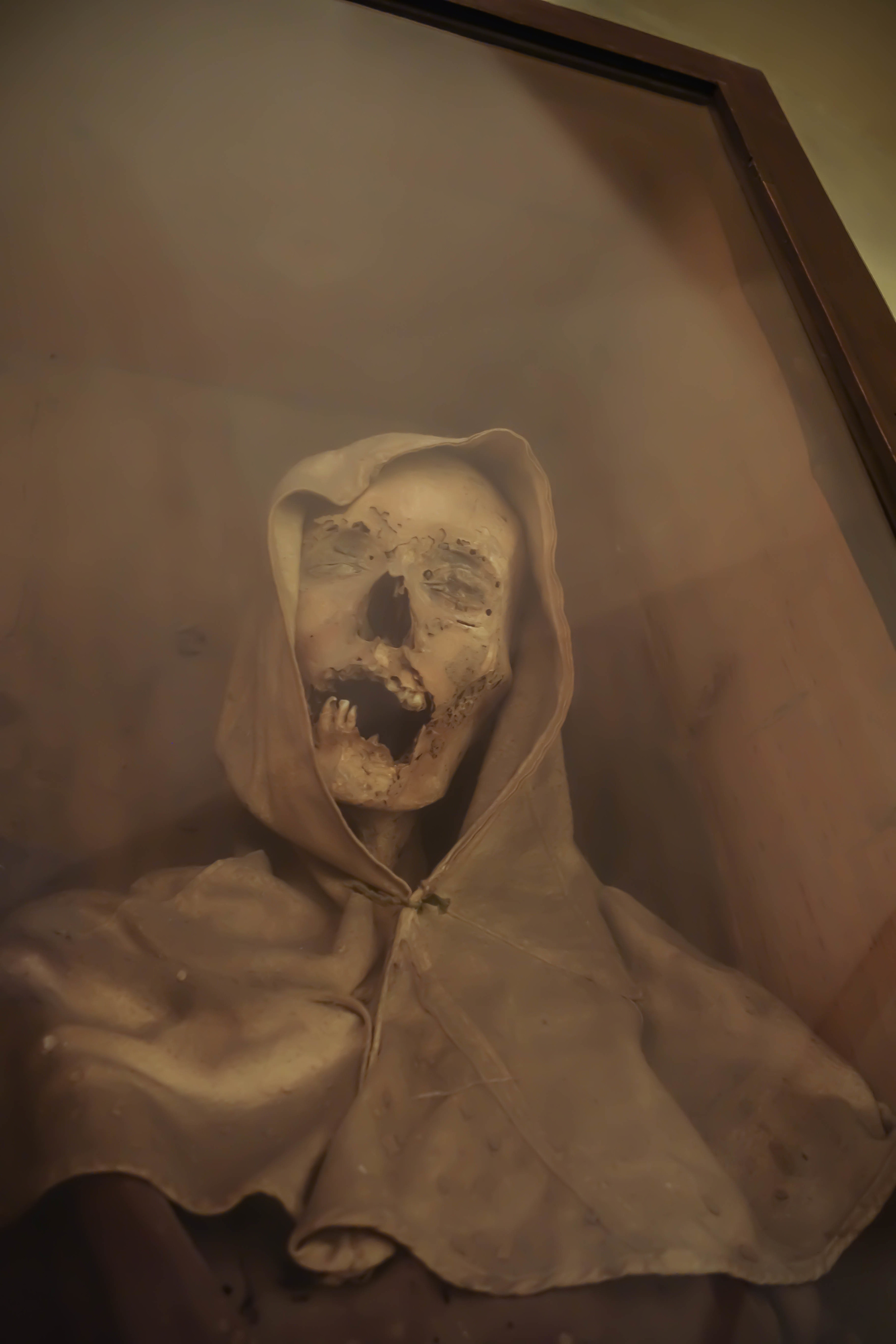

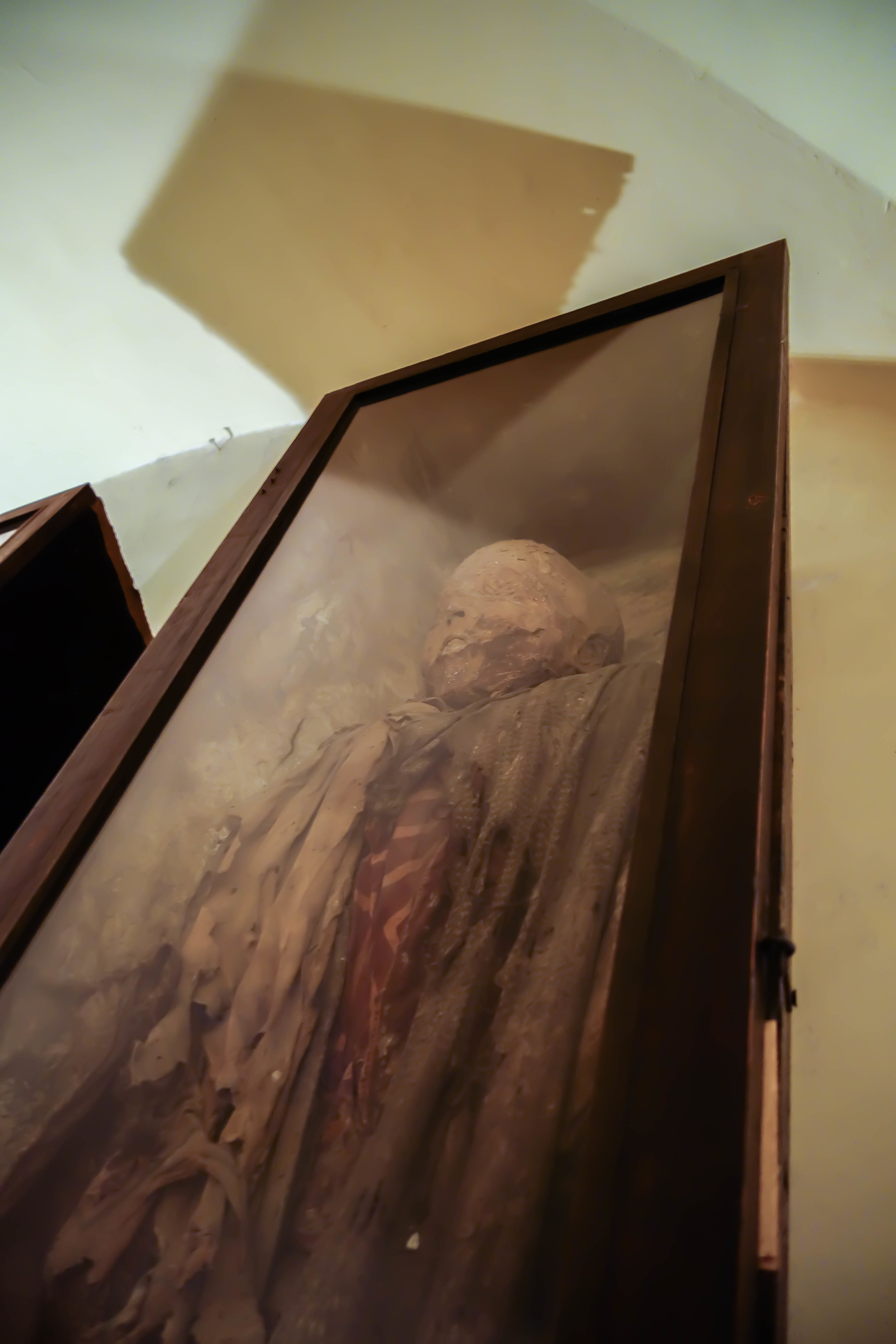

On the left side of the shrine is a marble niche containing the seated body of the man himself. The Plexiglas door between us has knee-high vents; I could kneel down and whisper my prayers to him if I wanted to. But I wonder if he could hear me—his ears are a little caved in. His skin is dusty brown and drapes over him like a limp paper bag, curling around whatever cartilage it finds. The bone on his chin is bare and the flesh on his cheeks sags so much it looks like he has a handlebar mustache. His ribcage peeks through his open sternum as if his skin were a shirt left casually unbuttoned. Combined with the flesh mustache, it gives him a 1970s look that I find kind of charming. He is conspicuously missing the tips of his toes. Thanks to the positioning of his hands in his lap, he is less conspicuously missing his penis, which was deemed immodest and amputated sometime before 1957, when its removal was mentioned in a letter from the archpriest of Bonito.

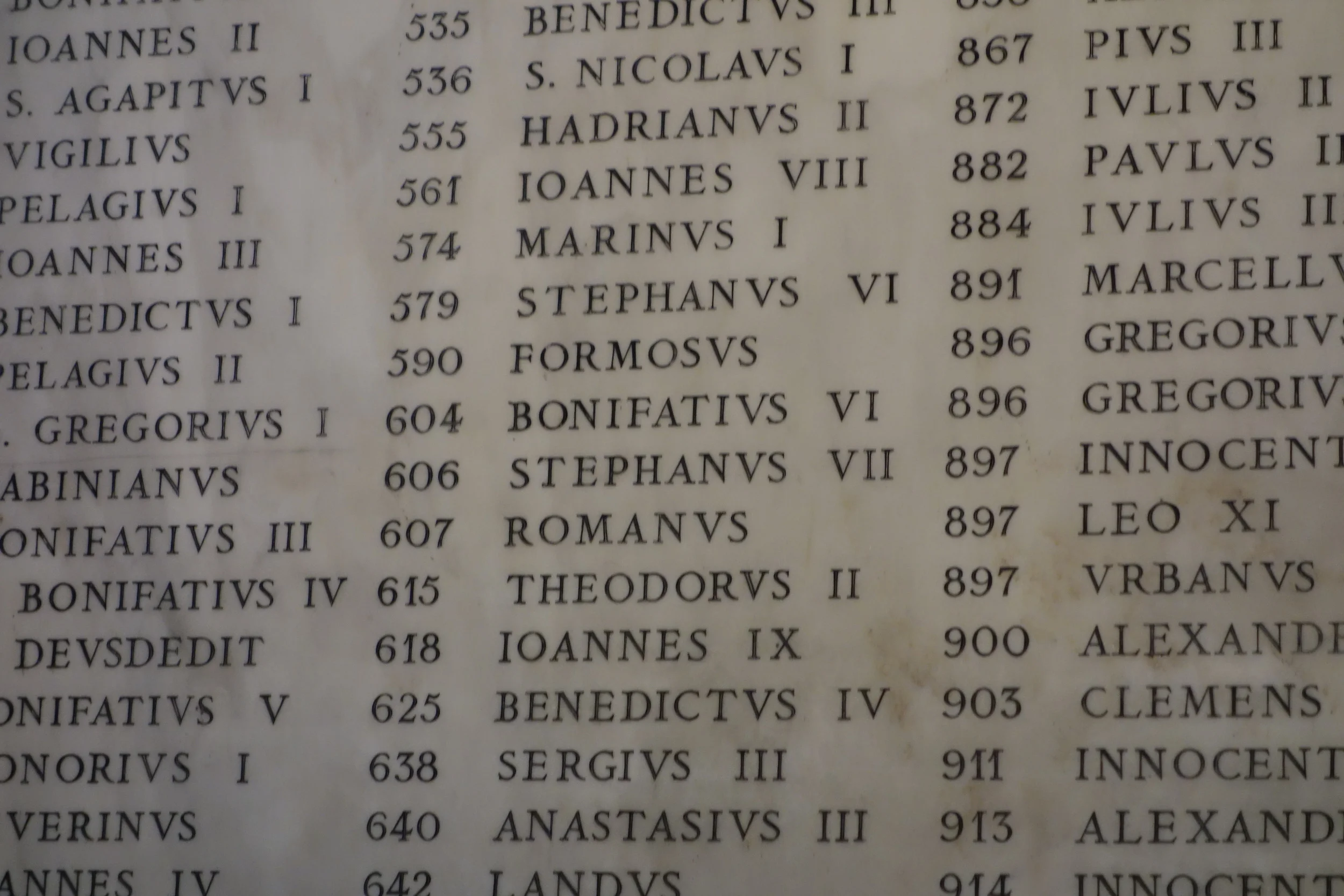

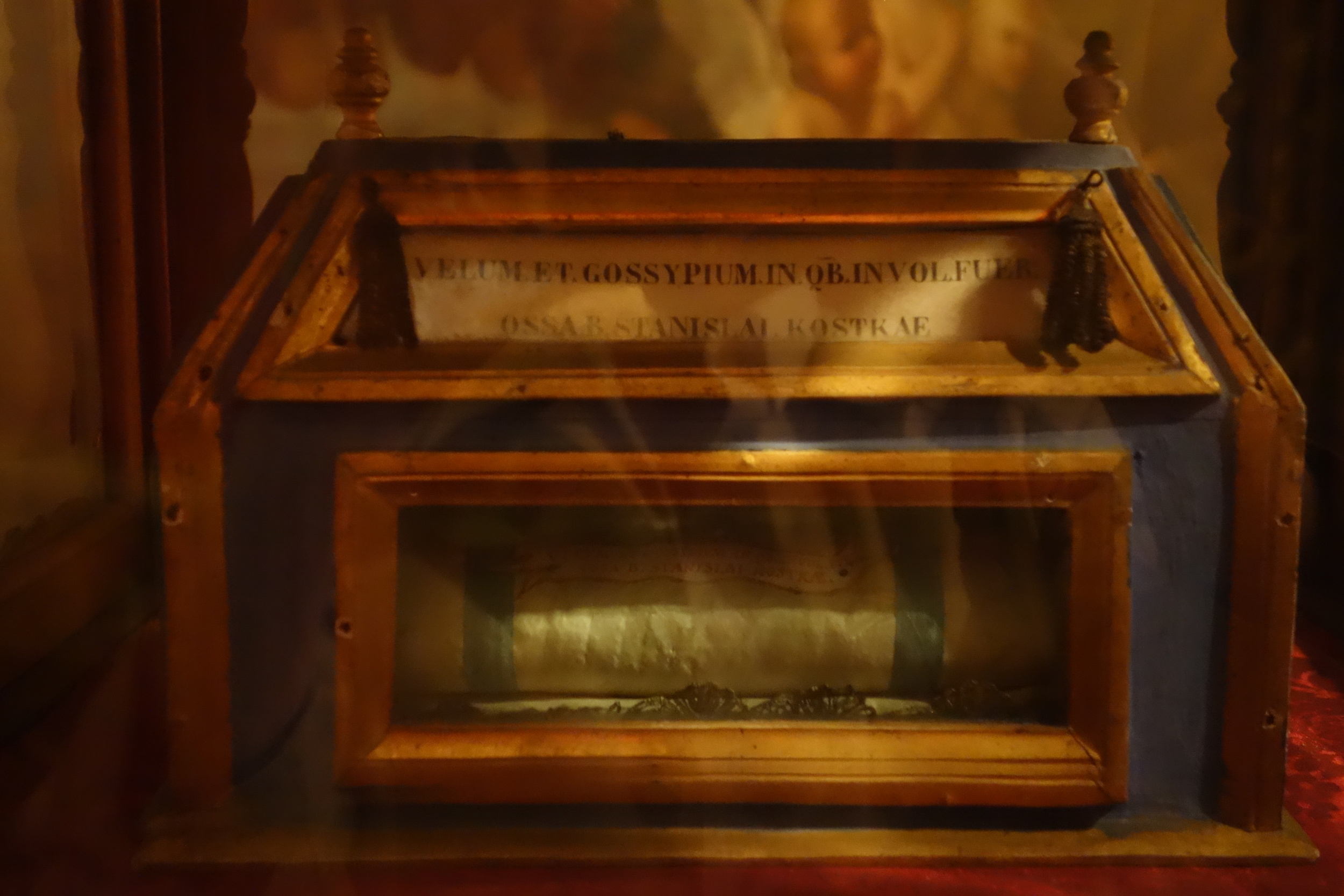

As an American, I find the sight of a corpse displayed like this a little shocking, but it isn’t so unusual. Catholic churches, particularly in Italy, often display the corpses of saints. In shrines like Uncle Vincent’s, I’ve seen skeletons in formalwear lying in Sleeping Beauty caskets, and gilded boxes containing holy hearts, tongues, heads, arms, toes, and almost any other body part imaginable. The reason is relic veneration, a type of prayer where people ask for a saint’s help in convincing God to answer their prayers. Because a mystical union is believed to exist between saints’ bodies on earth and their souls in heaven, the places where saints’ corpses (or at least parts of them) are kept become a kind of portal between heaven and earth. Plenty of churches are strewn with the holy dead.

According to the Catholic Church, saints (and their bodies) don’t actually have the power to grant miracles—only God can do that. But that isn’t reflected in the way relic veneration works in practice. Many Italian Catholics pray directly to the saints and rely on them to intervene based on their specialties. Some of the more common requests might sound familiar. If you’ve lost your keys, pray to Saint Anthony of Padua, patron saint of missing things. If you need to sell your house, pray to Saint Joseph the Worker and bury a statue of him in your yard. This is the tradition that also leads people to pray to Uncle Vincent.

Notes at the shrine of Uncle Vincent. Photograph by Elizabeth Harper.

Technically, the church rejects the idea of praying for direct intervention, but the clergy has a history of looking the other way to avoid alienating otherwise devout Catholics. In the gray area between folklore and orthodox Catholicism, these relationships with saints often become transactional: mortals promise prayers and offerings (such as ex votos) if the saints deliver what they need. But sometimes the prayers go unanswered. In America that’s when the faithful talk about “God’s plan,” but in southern Italy, they might just ask a different dead guy.

When a saint doesn’t respond at first, the petitioner may assume the saint is too busy. In that case, one option is to threaten the saint with replacement. (The citizens of Naples tried this in 1799 when they threw the bust of their formerly beloved patron, Saint Gennaro, into the sea after his dried blood miraculously liquefied in the presence of a French general and seemed to consent to the occupation of Naples. The citizens briefly replaced him with Saint Anthony, who proved ineffective against a volcanic eruption and was fired as well.) But if that doesn’t work, there’s another option that’s even more extraordinary. The petitioner may set her sights a little lower and direct her prayers to a soul in purgatory—a place where flawed souls on their way to heaven are purified in fire. The hope is that since the souls of these regular people are more plentiful and receive less attention than the saints, they will be happy to hear any prayer directed their way. They may respond even faster and be more likely to grant favors if the living also pray for a little refrisco for them—a temporary relief from the flames of purgatory that is supposed to feel like a cold drink on a hot day. It’s a perfectly logical solution: when the demand for Catholic souls in the afterlife is too high for heaven to accommodate, add to the supply by including souls in purgatory.

This is where Uncle Vincent is, spiritually speaking; people in Bonito generally believe his soul remains in purgatory. Yet the official doctrine of the Catholic Church says purgatory is only a temporary stop in the afterlife, one that souls usually try to hurry through. In orthodox Catholicism, people pray for the souls of people they know in purgatory in hopes of getting them into heaven faster; they never pray to them. In folk Catholicism, however, you don’t ask for favors and offer refrisco to the souls of people you know. Instead you pray to souls like Uncle Vincent, the purgatory lifer (or afterlifer).

In southern Italy, especially around Naples, there’s a persistent folk belief that if the names of the dead are forgotten, their souls can’t be prayed for and hurried through purgatory. These unlucky souls remain there forever, but it is believed they are particularly effective in answering prayers if contacted by the living—either through prayer or through the adoption and care of their anonymous remains. This is a helpful tenet in a region that has a lot of forgotten, nameless bodies heaped on top of one another after four hundred years of earthquakes, shellings, volcanic eruptions, floods, and plagues. Go into one of the caves around Mount Vesuvius and you’ll probably find a pile of potentially helpful new friends.

Vincenzo Camuso is one of these powerful but anonymous souls because Vincenzo Camuso probably isn’t Vincenzo Camuso at all. He was named long after he died, and there’s no record of where his name came from. No one is even sure when he died—it could have been the late 1600s or early 1700s based on a description of a confraternity robe his corpse used to wear. But he might have died as late as 1822, when a local court record mentions a Vincenzo Camuso who was charged with theft and general mayhem. Or maybe he was the Vincenzo Camuso from 1722 whose name appears in town records for making a payment on a vineyard. These theories assume that Vincenzo Camuso was his real name, but it could have been the name of the person who found his body or a name inscribed in a crypt that actually belonged to someone else.

What’s certain is that Vincenzo’s body is stuck in the seated position because Bonito’s Brotherhood of the Good Death was responsible for his burial. Members of this confraternity charitably cared for the town’s dead before undertaking was a secular profession. They were the ones who originally brought Vincenzo’s corpse to their crypt at the Oratory of Santa Maria Annunziata, where they placed him in a putridarium—a room where multiple corpses were left to rot on strainer seats until nothing but bone remained. The bones were supposed to be transferred to a final resting place after the decomposition process, but Uncle Vincent mummified instead—a curious but not uncommon occurrence, given the region’s arid climate—so he never made it that far.

Uncle Vincent, aka Vincenzo Camuso. Photographs by Elizabeth Harper.

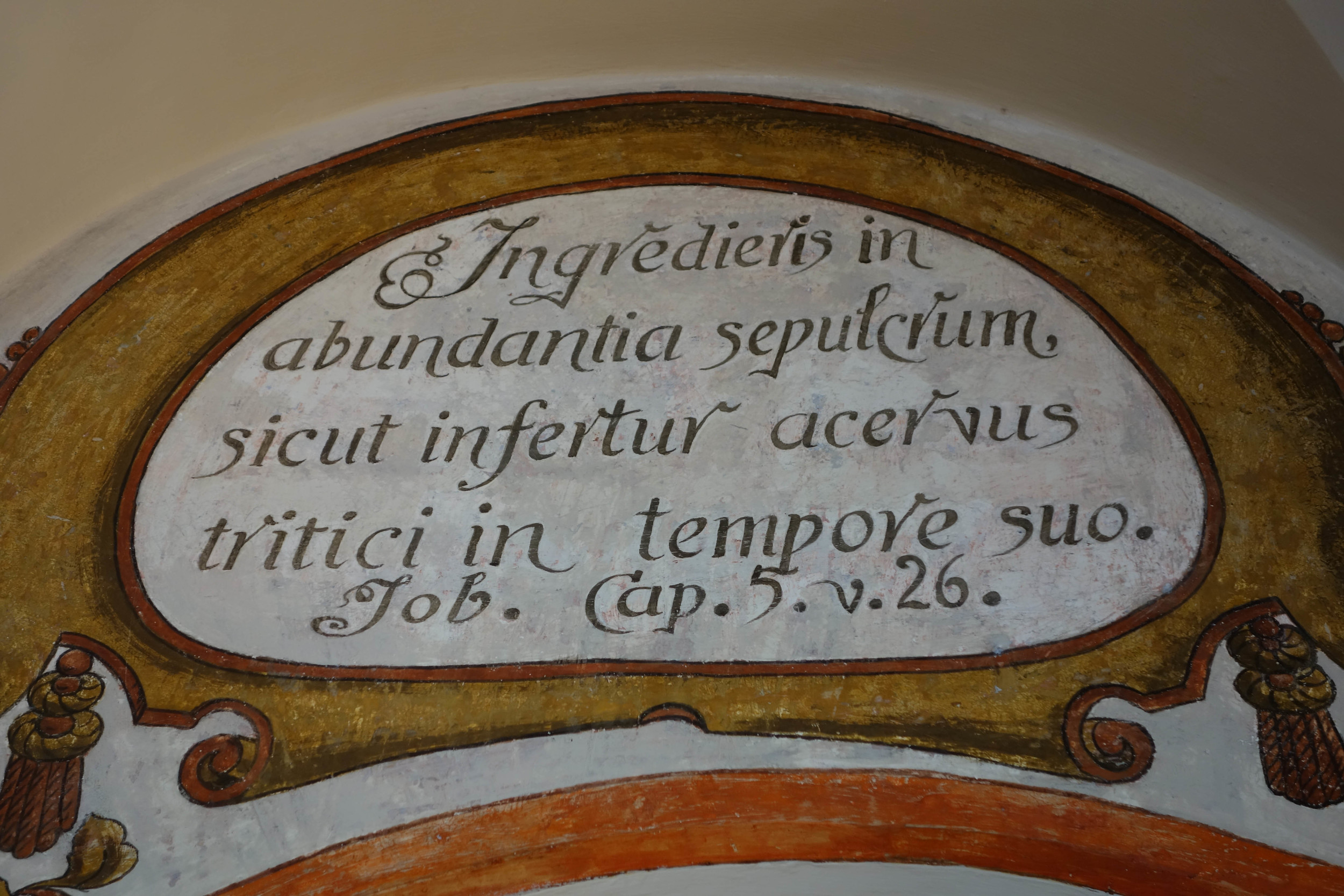

The Brotherhood of the Good Death operated for hundreds of years in Bonito, which means the only clue their involvement offers is that Vincenzo must have died sometime before 1849—the latest date the putridarium was used in Bonito, before Napoleon’s public health codes took effect. The French were repulsed by the Italian tradition of leaving corpses to rot in church basements, leading Napoleon to issue the Edict of St. Cloud in 1804 and force churches to abandon their crypts. But the law wasn’t observed until 1849, when all bodies began to be sent to the cemetery just off the main road on the outskirts of town. The Bonitesi, like many other southern Italians, had been reluctant to give up the putridarium. It allowed for a longer relationship with the dead that mirrored Catholic ideas about the afterlife. The putridarium resembled purgatory: a nasty, liminal space for the purging of sin or flesh. The final resting place for the bones was a private niche or mass ossuary that resembled heaven: clean and permanent. But Uncle Vincent never rotted away and thus never rested in peace—an appropriate outcome for the remains of someone who wound up stuck in purgatory. After mummifying in the putridarium, he began a long posthumous career as human decoration.

In the twentieth century, long after Bonito’s putridarium was retired as a place for bodies to rot, the crypt at the Oratory of Santa Maria Annunziata kept a few mummies and bones around for ambience and to remind the congregation to pray for souls in purgatory. Such human remains had no special powers and were thought to be no different than the crypt’s terra-cotta sculptures of people in the flames of purgatory—just another piece of inspirational decor. During this period, Vincenzo Camuso sat wearing a confraternity robe in a wooden niche alongside a woman who had also mummified. They remained there until the earthquake of 1930, when the woman disintegrated and had to be buried. The quake denuded Uncle Vincent of his robe, but his body stayed seated in his niche.

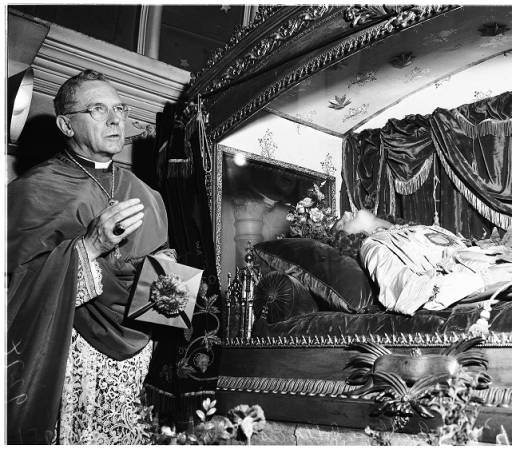

It wasn’t until 1950 that Vincenzo became unusually popular. The congregation built a new marble-and-brick niche for him, located not in the crypt but upstairs, on the left side of the oratory. On the right they built a similar niche to house the relics of Saint Crescenzio, whose bones were encased in a wax effigy of the boy martyr, beheaded at the age of eleven. The pairing seemed to imply that Vincenzo, a mummified nobody, was equal to a martyred saint. Maybe that’s why rumors began to spread that Uncle Vincent could answer prayers more reliably than Saint Crescenzio. People who prayed in front of the saint’s relics began to report that Vincenzo’s mummy called to them, asking for oil to keep the lamps burning near his niche. By the following year, a rogue priest at the oratory was secretly selling postcards with Uncle Vincent’s picture.

The priest was taking a serious risk. Catholic dogma holds that souls cannot become trapped in purgatory, and the idea of purgatorial souls answering prayers is considered superstitious at best for a layperson and positively heretical for a priest. Nonetheless, a number of churches will be happy to sell you postcards of allegedly miracle-working bones still in their crypts. I bought a few at the gift shop for the church of Santa Maria del Purgatorio ad Arco in Naples, including one of a rhinestone-tiara-wearing skull named Lucia known for finding suitable husbands. These postcards ostensibly help pay for the churches’ preservation, but they also turn what used to be powerful relics into museum exhibits, things of the past that can now be seen only on a tour under a docent’s guidance. It’s hard to interact with the bones spiritually if they’re commodified for tourists. Though they seem to harken to a forbidden form of veneration, in fact they represent a crackdown on the southern Italian practice of worshipping forgotten souls in purgatory.

But in the 1950s devotees of Uncle Vincent treated his postcards like prayer cards and began thanking him for the favors they believed he was granting. At first, Vincenzo’s acolytes kept his oil lamps burning, but soon they had electric lighting installed in his niche. People left gold and silver jewelry, charms, candles, letters, money, and photographs. By May 1962 the local bishop warned that Vincenzo Camuso could be the center of an illicit cult. If the priests wouldn’t move him from the oratory, he would issue a bull and move him by force.

Ex votos at the shrine of Uncle Vincent. Photograph by Elizabeth Harper.

It never came to that. In August 1962, another earthquake hit Bonito. A number of sources claim that this destroyed the oratory where Uncle Vincent sat, but some people deny it, explaining that diocesan authorities ordered the destruction of the oratory despite minimal damage to the building. Given the bishop’s threat, it’s easy to guess why. Saint Crescenzio moved to the new parish church, but Uncle Vincent found another way to persevere. A group of Bonitesi who had immigrated to America paid for the reconstruction of a small part of his old oratory. This is the little shrine where Uncle Vincent sits today.

Despite all the friends and admirers he’s made over the years, Uncle Vincent has a well-known dark side that unnerves me a little when the two of us are alone. When he’s not healing people in the hospital, he seems to enjoy sending people there. Doubt him and he may beat you with a stick or a human bone or push you into a ravine, as he supposedly did to a mason who cursed him while working on the restoration of his shrine. Another supposed victim was the fascist mayor’s wife, who covered him with a sheet because she was ashamed of him. People say Uncle Vincent beat her to death in her sleep and then came for her young husband a year later. It’s a good story, but it’s easily disproved. The mayor in question would have to be Attilio Grieco. He died of a stroke at sixty-seven, and his wife didn’t die until twenty-three years afterward. Uncle Vincent seems like a particularly violent kind of saint, a revisionist capable of exorcising fascism and nonbelievers from the pages of Bonito’s history.

One might wonder if the Uncle Vincent phenomenon is simply a case of mass hysteria—an isolated town that has animated a corpse with little more than the power of collective imagination—but that wouldn’t explain his love of travel. A woman from Catanzaro, a town about five hours to the south, said she had never heard of Bonito until Uncle Vincent visited her in a dream in 1975. He introduced himself and asked her to pray for the salvation of mankind. Another local legend is that his spirit went to Venezuela in 1962, speaking in Bonitesi dialect through a medium at a séance. Uncle Vincent’s appearance at a séance seems appropriate: his democratic appeal, and that of other souls in purgatory, recalls the Spiritualist movement, which popularized the séance and was led by women who lacked access to power in traditional society and religion. In Uncle Vincent’s case, his power can be accessed by people who feel left out of the Catholic Church with its patriarchal and class-based power structure.

I pick up a few prayer cards printed with a midcentury photograph of Uncle Vincent and take the shrine’s key out of my pocket as I prepare to leave. Then I notice a second key on the ring. It is small, as if it belongs to a safe deposit box. The only other lock in the shrine opens the Plexiglas door that separates me and Vincenzo. Now I notice the photos and letters carefully arranged around his body and see the gold necklace that someone had placed in his hands, the thin chain wound around his fingers. I could open that last door, but to what exactly? A violent punishment? A divine favor? Or maybe access to a place where this world and the next seem a little closer. But I don’t need any special powers to get there. I just have to befriend the naked man on the other side. I don’t unlock Uncle Vincent’s door, but I feel a tiny stirring that asks me to keep his lights on as I leave, locking the door behind me.

Rest In Beauty: an Interview with Swide Magazine

Originally published on Swide by Jonathan Bazzi.

An interview with creator of All the Saints You Should Know, a fascinating photographic project on the body-relics of Italian saints.

In Christianity, the body takes on a incredibly powerful value, the idea of ncarnation makes Christian culture particularly sensitive to the body as the site of representation of the sacred, of asceticism and spiritual transformation. The long tradition of saints and martyrs in particular frames this centrality of the body as a means of contact with the Divine. With martyrs, fasts, mystical ecstasy, and sacrifice of one's own life the Christian God marks the flesh and penetrates the physical dimension of the person by forming a set of signs and symbols that make Christianity one of the most visually and aesthetically powerful religions, even to the profane eye. The photographic work of Elizabeth Harper is situated in this evocative dimension, and consists of a photo blog that gathers together beautiful pictures of the seemingly uncorrupted bodies of several Italian saints, especially focusing on those stored in the churches of Rome. We chatted with her on the themes of her work, her artistic and literary influences and the meaning of the body in religion and art.

Let’s begin from the story of your project, the blog All the Saints You Should Know: when and how did you started? And what about your future, do you have any plans or dreams?

I began this project because I love art but going to art museums while I was traveling was unsatisfying. Too many collections felt like they could be moved from one white room into any other white room. That felt like the antithesis of travel so I started looking for places I could see art in situ—anywhere that mixed history and art. What I was really searching for was the old way of displaying art—in a kunstkammer or wunderkamer—someplace where art can be grouped with all the other types of wonder and beauty in the world without much thought about the boundaries between subjects or even accepted definitions of art or beauty. That type of collection is almost a type of theatre (maybe the most local and ephemeral art) because the collector’s point of view and personal story is on display in the collection and it’s unapologetically a kind of narrative about a very particular time and place. That is actually what I found in churches. There, art is juxtaposed with all of these other items: human bones, wax saints, icons, even taxidermy and scientific devices. Together, they’re all telling the fascinating story of the Church: the individual parish and the greater Catholic Church as a whole. But there often isn’t much information available and a lot of people either didn’t know these places exist or they’re confused or a little intimidated by coming into a church. I realized that since I had grown up Catholic and I had these interests, I had enough information to start teasing out the hidden stories of these objects and places. That’s really all I want to do—excavate stories and history from these collections and allow others to appreciate them through writing, lectures and photographs.

Who inspires you? Did you have any models, teachers or examples that helped you defining the direction of your work?

I’m continually inspired by the Romantic writers who came to Italy: Goethe, Chateaubriand, Stendhal, Byron and the Shelleys. I love reading their diaries and letters because they were foreigners here like me and I think they came to Italy to access the sublime. On one hand here you have the pinnacle of human achievement and beauty: the Renaissance masters, the Baroque architects. But there is also the persistent memento mori—the ruins of the Roman empire, seeing the old pinnacle of human achievement in decay. You see this in the very architecture of the churches too. The upstairs is triumphant—aesthetic perfection, and the downstairs is decay—the decay of bodies in the crypt, the decay of pagan temples demolished and built over, the disorder of history collapsed in on itself in the scavi. This kind of sublimity is hard to access in the US because we have the tendency to want only beauty and no horror.

Your parents are Italian: what's your relationship with Italy? Do you have any favourite places in our country?

My mother is Italian, her family is Sicilian. But my favorite place is Rome. It’s just so much of everything there. I think of Rome as a kind of memory theatre—a cabinet of miniatures that could possibly reveal all the knowledge in the world if someone were able seek it and put it together. I think about that often when I’m walking through the city. Sometimes I’ll step on a cobblestone or stone in a floor and feel it shift, it makes a hollow sound. I’m reminded that there’s always more that’s hiding underneath. So I dig deeper and try to see every little detail that leads to another story. I ask to have the doors unlocked… I try to put it all together and see what it can tell me about life today. My favorite place in Rome, that isn’t a church, is the Mario Praz house. If I could move in I would. I’ve drawn on so much of his work and his house embodies everything I love intellectually and aesthetically about Italy.

Your work is related with religion, church and saints. What kind of role does spirituality play in your life? Did you have any spiritual or mystical experience?

When I began writing about these things, I made a conscious decision not to address my spirituality in my writing. I prefer to keep it private, largely because I don’t want people to get hung up on if they agree with me about religion or not. I want the stories behind these objects to be enjoyable for everyone with any kind of interest in the Church— whether they're a nun or a secular academic. That being said, I’ll tell you that in my travels, I’ve often found myself deeply moved, sometimes to the point of lightheadedness or tears, but I’ll leave it open to interpretation whether that’s mystic ecstasy or Stendhal Syndrome.

The human body seems to be very important in your project: what's your vision of the body in art and visual culture? Did you study anatomy or drawing?

It is and part of that is inextricable from the Catholic Church. It’s fundamentally a corporeal religion but it’s paradoxical: the Word is made flesh but the flesh also harbors sin. I think that aspect is particularly accessible to women who still deal with the male gaze and are used to having judgments leveled at their bodies and how they present them. That’s one of the reasons that I’m particularly interested in female mystics from the Middle Ages. At first glance, they seem otherworldly but when I looked a little deeper I saw pieces of myself and seeds of my own insecurity and shame in these women. They’re at once so deeply human yet supernatural and their bodies are testament to that—from the scars of compulsive mortification of the flesh in their living bodies to the perfection of their incorrupt corpses in death. I find their struggles and solaces endlessly relatable. It’s funny you should mention drawing. I took four years of figure drawing classes in art school and really enjoyed it but I never connected it to this particular obsession of mine.

Do you have a favourite saint?

I love St. Catherine of Siena. She’s well known for her mysticism but her writing also reveals a smart and opinionated young woman with a sarcastic streak. She also battled with herself for absolute control and perfection of her body. Her life and relics along with the places they rest in Rome and Siena are perfect examples of the type of history and humanity I hope to uncover by looking around in churches.

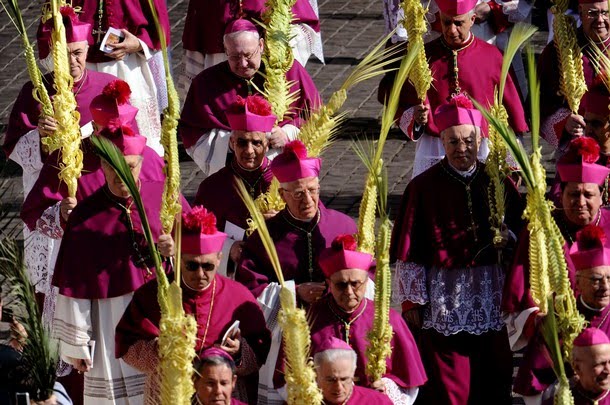

The Passion of Holy Week

Originally published on the LA Review of Books Blog.

As a child I used to condemn Jesus to death at the start of every Holy Week on Palm Sunday. Our priest would read from the gospel of John and he’d ask, lightly in character as Pontius Pilate, what we should do with the son of God. “Crucify him!” we’d say, with varying degrees of enthusiasm. That was what the script in our missalettes said, but I wished I could say something different. My religion teacher had taught me what happened to a crucified body — how the nails pierced the space between the wrist bones, how the body slumped forward from exhaustion, and how this probably pulled the arms from their sockets before asphyxiation. It upset me to see everyone at church, even the nuns, call for anyone’s death this way so at some point I decided to only mouth the words, failing to grasp the point of the spiritual exercise but sincerely trying to not kill Jesus again this year.

I think it was these early memories that led me to Zamora to see Spain’s oldest Holy Week celebration last year. It began two days before Palm Sunday and ended nine days later on Easter. Wikipedia advised me that unlike the celebrations in bigger cities, this one would be somber and contemplative. Here, participation went beyond a call and response at mass. About half of the residents of Zamora were members of one or more of the city’s 16 confraternities, some of which have over 1,000 members. For most of the year the confraternities function as loose social and charitable clubs but during Holy Week they mount 17 crucifixion-themed processions which recall their original purpose — a way for members to atone for their sins.

During the processions the confraternity members wore floor-length robes and capes. Some had a simple hoods but most included caperuzos, the iconic meter-high conical hats with fabric flaps that cover the wearer’s face. Let me get it out of the way: the confraternities looked a lot like the Klu Klux Klan. When they trudged through the city at night carrying torches and crosses, it didn’t look good to an American like myself. But the people of Zamora have been celebrating Holy Week the same way since 1279 and they aren’t going to change for a bunch of 19th-century racists. Originally, the caperuzos mimicked the hat used to shame criminals and symbolically shamed the wearer for their sins. The hoods protected their identity so no good deeds done as penance could be attributed to anyone.

The highlights of the Holy Week processions were the pasos — wooden parade floats carried on the shoulders of confraternity members with life-sized figures illustrating the Passion of Christ on top. Most were bloody: Jesus crowned with thorns, Jesus stripped and tortured, Jesus as a corpse with his body rendered in a light green. Everyone in Zamora found a spot with a good view of the pasos hours before the processions started. We amused ourselves by checking our phones or eating packets of sunflower seeds. The teenagers next to me texted and met up with their friends, planning for a night when curfews were suspended. At this point we were midway through the week so the festivities were nearly continuous with a midnight procession ending just as the five a.m. procession began.

I got a text from a friend who had been to Zamora while studying abroad. “How’s Holy Week?” she asked, “Is everyone still making out?”

“YES,” I replied.

Wikipedia didn’t alert me to this fact, but it was true. The processions that night would be a lot like the ones before. They were solemn and completely silent events except for a single drumbeat or a chanted funeral dirge. But as the night wore on, couples pulled each other closer as the temperature dropped. High school girls ditched their sweaters and compensated by getting closer to the boys, the more enterprising of whom had brought blankets, ostensibly for warmth but also good for shielding wayward hands from the eyes of the Virgin Mary. She floated by after midnight on her paso, cradling her dead son, escorted by hundreds of hooded men in black.

Anyone tempted to blame their less-than-reverential behavior on the fact that these kids were millennials or whatever the Spanish word is for “kids these days,” only had to look as far as the town square to see that a certain amount of fooling around wasn’t just tolerated but had somehow been a part of the experience here for a long time. Huge black and white photographs of Holy Weeks gone by were hung on the sides of the buildings, mostly highlighting how little had changed in Zamora except for fashion. In one of them, a girl straddled a boy’s lap. Their faces were buried in a deep kiss and they pulled each other closer by the waist and the neck. They seemed oblivious to the camera and even less aware of the life-sized Jesus directly behind them, dragging his cross to Golgotha.

This picture of eroticism in the face of an execution emphasized a paradox that I had noticed all week. Wherever there’s death, there’s decadence. It was threaded through every aspect Holy Week, though often in less salacious ways. For the whole week in Zamora, no one seemed interested in work except for the people selling food, drinks, candy, and cigarettes, which everyone — including the sellers — had bottomless appetites for. But the specter of death that marched by us tainted even these simple pleasures. Their consumption was anxious, more in line with the excesses of a last meal than the celebration of a feast. It was as if we collectively wondered, if even God can die a painful and humiliating death, then what might be in store for all of us? What might our fellow crowd-members say if it was our fate that was in their hands? Or more chillingly, I asked myself what I was capable of. Me, the one who said “crucify him.” We all knew that the apex of our own cruelty, and the cruelty of our fellow men, was our own death. So while the human sacrifice we demanded in church played out in the streets, we indulged like dead men walking in tapas and wine bars that stayed open until dawn. We reached out to each other for what seemed like it might be one last time.

The connection between decadence and death has long and sordid history. But I don’t think it’s been better examined or explained than by the French philosopher and sometimes dirty-book-writer, Georges Bataille. According to Bataille, a life that’s spent dedicated to productive activities — the kind of everyday work left undone during Holy Week — is a life that’s obsessed with its own legacy which can live beyond a human lifespan. This is a kind of immortality and a life that’s dedicated to immortality is actually obsessed with the avoidance of death. This is a life that’s denied. So according to George, to live is to practice dying, or to die just a little. There’s a reason the French called an orgasm la petit mort.

In Bataille’s mind, the kind of sex that allows you to die a little (which is not the kind intended to make babies to carry on your lineage) is an act of violence. It violates our borders. It’s a loss of control — a moment when people’s innermost places react without the consent of the brain, puppeted by another. It’s horrifying and embarrassing, but we do it because for a moment, we’re not alone. When we obliterate the boundaries of our body and the parts of ourselves we call our identity, we find the ability to connect to something greater than petty self-preservation. In the case of sex, we connect to another human being. But sex is only practice for the more violent obliteration to come. We lose control of our bodies again when we die and decompose. At that time, we’ll be stripped not just of our clothes but our flesh. It’s more horrifying and more humiliating, but by doing so, we’ll finally become one with the earth and with the history of the world, something much bigger than an infinite number of partners.

I’m sure I was thinking about death when I started talking to a confraternity member outside the church in the main square. He was still wearing his robe and carrying his red cone hat from his procession a few hours earlier. We talked until the midnight procession went by and then ducked into a bar around one a.m., though the procession would still wind through the city until sometime after three. The place was full of 20 and 30-somethings back in town for Holy Week and the scene reminded me of the bar near my high school on the night before Thanksgiving. Everyone was both a local and a tourist. Miniature reunions happened whenever someone walked through the door and no one was too eager to get back to their parent’s house.

The confraternity member and I got a drink and he told me about the subtleties of all the different processions while I took notes. According to him: the group with the black velvet robes were snobs. The ones with the hoods that look like sacks instead of cones were working class and a lot more fun (he was a socialist, so I took his characterizations with a grain of salt). All the guys who carried the pasos in his confraternity were year-round drinking buddies. There was no rehearsal for the parades. Sometimes people decided to march barefoot, not because they were particularly pious, but because it was actually easier than walking on cobblestones in dress shoes and it’s the kind of thing that would make your mother proud.

At some point after our first drink, I stopped taking notes. After our second drink we hated the same things, and were eviscerating Hemingway for being a jackass in Spain. After our third we were in full Hemingway mode: pressed against a medieval city wall and engaged in heavy gonzo cultural anthropology.

Eventually I rediscovered my bearings and my boundaries and we parted, going our separate ways for the night or at least whatever was left of it. I snuck past another couple on a park bench who seemed to have no intention of doing the same. I walked through Zamora as the black sky turned navy and passed a group of kids in a parking lot. They were blasting Ed Sheeran and still drinking red wine and Pepsi out of plastic Solo cups. They were dazed, oblivious to the impending day but in that moment I couldn’t muster judgment — I had obliterated myself in only a slightly different way and anyway I was pretty sure my skirt was on backwards.

I went back to my room and slept through the five a.m. procession, barely pulling myself together for the one at nine. He and I didn’t see each other again and processions wore on, each a little more like the next until cannons fired on Easter morning, shaking everyone, including me, out of their grasping, melancholy haze. Folk bands played in the streets and order was restored to our briefly apocalyptic world. Our transgressions were set right again: life became productive, we returned to polite self-sufficiency, and even the God we killed rose from the dead and forgave us all. Of course we had known this would happen. We do it every year because we need a little death in order to stay alive.

The Days of the Dead: A Dispatch from Rome

Originally published on the Morbid Anatomy Museum blog.

Halloween in Rome is a quiet night even when it falls on an unusually warm Saturday like it did this year. A handful of kids trick-or-treated at the shops around the Campo de’ Fiori dressed as some pastiche of a corpse, a vampire or a witch and the study abroad students drank in the same bars they always do, but this time with light-up devil horns or a cape. I took a midnight stroll to the Ponte Sant’Angelo to see if the ghosts of any criminals that were executed there from the 12th to 19th century felt like celebrating, but it seemed they had no use for an imported American holiday. I wasn’t really disappointed though because on November 1st, as Americans woke to stare Christmas in its gaping maw, Italy began a two-day Catholic holiday devoted to remembering the dead.

November first was All Saints’ Day, a day devoted to the holy dead—the saints and martyrs in heaven. This is a holy day of obligation, meaning practicing Catholics are obligated to attend mass, so a lot of shops and restaurants were closed. But one of my favorite bakeries was open so I stopped and bought some almond cookies made especially for the holiday called “beans of the dead”.

Beans in Italy have a long and curious history as a food that harbors symbols of both life and death, in the form of supposed dead souls trapped in the bean and in the way beans swell with life like pregnant women. Beans, beans, the paradoxical fruit… Writers Sarah Troop and Colin Dickey have both written fascinating pieces about them and you should absolutely read both of their pieces.Fortified by my bean-cookies and a double espresso (the Italian breakfast of champions) I set out on a walk through the city until I got to the Campo Verano cemetery, just outside of the Aurelian walls that surround the historic center of Rome. This is where Pope Francis was saying mass today. The cemetery was dressed for the occasion—relatives had spruced up graves with pots of mums and votive candles.

A growing crowd trickled in and I figured I would try to find a decent place to stand on the outskirts and maybe I could catch a glimpse of the pope. I was unsuccessful. Instead, I got caught in a group of gung-ho nuns who were going to see il Papa come hell or high water (though either scenario seemed unlikely). When Vatican security officers began letting a few people into the gated seating area, it became clear I had two options: go with the flow or die in a nun stampede.

I chose to live and wound up with a great seat for the papal mass. The sun set as incense wound around the tombs and I was thankful to survive… for another day anyway.

That night, I chatted with a friend who jokingly said that the only way a papal mass in a cemetery could be more “me” is if they dug up the graves and sat the corpses around me. I replied in all seriousness, “No, that’s tomorrow night.”

The day after All Saints’ Day is All Souls’ Day, a holiday devoted to all the other Catholic dead—the regular Joes and Giuseppes who might be in heaven or who could be working their way though the fires of Purgatory where souls are purged of sin before being admitted to heaven. This holiday is somewhat less important in the eyes of the Church, but what it lacks in official holy obligations, it makes up for in popular devotion.

Around 4pm, as the starlings began their ritual of ominously swarming overhead, I went to Holy Mary of Prayer and Death, an oratory on Via Giulia that you can’t miss thanks to the huge, laughing skulls and skeletons that decorate the façade year-round. Any other time, you’re likely to find the doors locked but today, a nun kept a side door open and welcomed people inside. Drop a few coins in her basket and she’ll be your own personal Charon who takes you to the land of the dead. She escorted me down a narrow hallway lined with tombstones to what remains of the oratory’s crypt and cemetery.

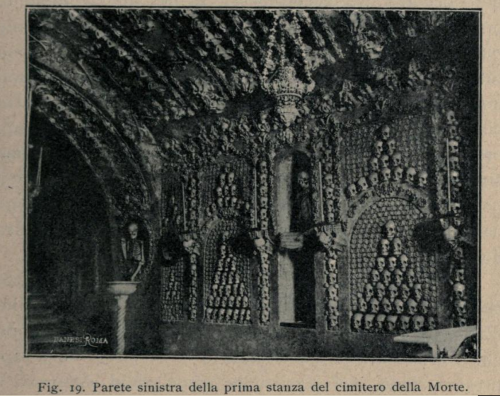

The previous day’s cemetery had the pomp and formality you would expect from a papal mass. The elegant, 19th century tombs were built when Napoleon issued his public health codes which mandated that burials take place outside the city walls, under sanitary, modern conditions. These laws were put into place to obliterate macabre little ad hoc crypts like this one. Here, vertebrae were made into rickety electric chandeliers. Skulls were mounted on the wall to form a cross, or stacked in cabinets or piled onto the altar. A stray ribcage slumped in a corner. I recognized him from a previous visit, when he used to have a skull and had been propped up on a rod like a human pogo stick. Time keeps on slippin’, I suppose.

I’ve done a bit of research on this oratory so I decided to offer a little context to a group of confused and slightly unsettled folks from Boston who came down. They had just been walking down the street and came in because the nice nun told them to. I explained that this confraternity used to walk out to the countryside to collect the bodies of dead migrant workers from the fields. They gave them a Catholic burial in the crypt here, but a Catholic burial doesn’t actually require you to stay buried. So the bodies were eventually dug up and used as decoration or better yet, as actors in the theatrical scenes the confraternity staged for All Souls’ Day in the 18th and 19th centuries. If you want my full tour, you can read this previous guest blog I wrote which includes old photos of what the crypt looked like in its heyday.

The nun on door-duty seemed to enjoy my little tour because she sent a few more people to talk to me and by this time I was leaning into my fantasy job as Italian crypt-docent. (Please let me know if you hear of an opening in this field.) I would’ve stayed but I looked at the time and realized I had to run. There was no way I was going to be late for my next visit.

I hoofed it over to St. John Calibyte on Tiber Island for a very special once-a-year treat. On the night of November 2nd, and only then, you can join a candle-lit procession for the dead and see the Sacconi Rossi crypt.

The Sacconi Rossi were a confraternity similar to the one at Holy Mary of Prayer and Death, but they worked inside the city limits, picking up the bodies of people who died on the streets and fishing poor souls out of the Tiber. They offered these bodies a similar type of temporary burial followed by an eternity as crypt decoration.

Sacconi Rossi is a nickname and it literally means “red sacks” because they wore bright red robes. Their official name is “Devotees of the Brotherhood of Jesus Crucified at Calvary and Holy Mary of Sorrows” so you can see why they needed a nickname. They don’t really exist as an organization anymore but every year for All Souls’ Day, people from the parish of Santa Maria dell’Orto don the red sacks and honor the unknown and forgotten dead. After a mass, the priest and the red-robed parishioners led a candlelit procession down to the banks of the Tiber. There, the priest threw a wreath of white flowers into the river to honor all the unknown people who died. Then the procession went back up to the piazza were the crypt was unlocked for its annual blessing and visit.

In this crypt, the bodies were so old that the smaller bones had all crumbled into dust. What remained was mostly toothless, jawless skulls stacked on tibae and femora. The only whole-ish skeleton was missing his feet and wore the red robe of the confraternity. He was splayed out on the ground between two pews, inviting everyone to take a seat and ponder him. As David Sedaris says in his essay, Memento Mori, “The skeleton has a much more limited vocabulary, and says only one thing: ‘You are going to die.”

A cloud of incense filled the crowded rooms of the Sacconi Rossi crypt and dozens more red votive candles burned as the priest sprinkled holy water on the bones. A few people joked under their breath that it was so hot that it was a shame that only the dead were getting sprinkled. But that’s the way it is. This is their day. Every other day is for the living.

Our Adored Cadavers

Originally published on Hazlitt.

On an exterior wall of St. Sebastián’s church in Madrid, there’s a little tile sign dedicated to a poet. “In this church,” it reads, “Lope de Vega Carpio was buried in the year 1635.” The sign is decorated with a sketch of the church to which it’s affixed, showing the building in its pre-1930s state, before bombs leveled it during the Spanish Civil War. The shape of the building is still recognizable, but it’s drawn from the back and features a cemetery where an outdoor flower shop stands today. There is something funereal that clings to that flower shop. It’s in the black iron fence and the floral arrangements. It’s in the new black sign arching over the entrance that says, “Never stop dreaming.” A harmless cliché, but once you know the history of the place, it reads like a memo to the bodies once buried below. Never stop dreaming. Please, don’t let anyone disturb you from your eternal sleep.

María Ignacia Ibáñez was a body who should’ve stayed at rest. She was buried here, at St. Sebastián’s, in 1771, after dying of typhoid at the age of twenty-five. She was a famous actress in Madrid, but despite her success, she didn’t get a little sign like Lope de Vega; she isn’t even included in the church’s list of notable deaths next to other artists, architects, and writers. But this is unsurprising: the church would probably like to forget about her, her gravesite, and most of all, her boyfriend, José Cadalso. This is thanks to Cadalso’s prose poem, Noches Lúgubres (Lugubrious Nights), which he wrote after her death. It’s the story of a man just like himself who breaks into a cemetery just like St. Sebastián’s and attempts to dig up the corpse of a woman just like Mariá Ignacia.

Lugubrious Nights was a grisly piece of writing, but it was also an influential one; if Cadalso began work on it the same year as María Ignacia’s death, as some scholars speculate, then it was easily the first piece of Romantic literature in continental Europe, preceding even Goethe’s sturm und drang classic The Sorrows of Young Werther. Cadalso’s gloomy body snatcher could also be seen as the first Byronic hero, years before Lord Byron was a gleam in his father, Mad Jack’s, eye. But despite the fact that Lugubrious Nights was ahead of its time, it wasn’t quite as innovative as it seemed. A subtitle from some early editions hints at this: Imitating the Style of those that Dr. Young Wrote in English.

And in this case, style didn’t simply refer to form. Dr. Young’s poem featured a familiar plot line: a man, very much like the author, breaking into a cemetery.

Grief Changes a Man

The Reverend Dr. Edward Young was an English poet, but not only was he not a Romantic, he also wasn’t the type of fiend who would make a hobby out of pilfering bodies from cemeteries. It’s true that, as a student, he blacked out his windows and worked by candlelight radiating from a human skull, but he saw this proclivity as artistic Adderall, the work-habit of a bona fide poet that could help him catch up after slacking off at school. As an adult he outgrew his goth phase, settling in as a serious Protestant and even becoming a royal chaplain, his poetry evolving in the Neoclassical style. Etchings of him show a Hostess Donette of a man—a white powdered wig on a doughy face, sitting on a doily cravat. His body of work mostly featured poems with long, fawning dedications to patrons who always seemed to go broke just after hiring him. (An embarrassing habit—as Jonathan Swift quipped, “Young must torture his invention/To flatter knaves, or lose his pension.”)

Which is how Young likely would’ve been remembered, and quickly forgotten, had he not confessed:

With pious sacrilege, a grave I stole,

With impious piety, that grave I wrong’d

Short in my duty, coward in my grief,

More like her murderer than friend, I crept

He wrote those lines in The Complaint: or, Night-Thoughts on Life, Death, and Immortality (commonly called Night Thoughts), which he published in nine parts called “nights” from 1742 to 1745. This passage comes from the poem’s famous third night, wherein Young writes himself in as a man who breaks into a cemetery with the corpse of a young woman named Narcissa in tow. Alone and distraught, he buries the mysterious woman secretly in another man’s grave.

Night Thoughts is a classic example of Graveyard Poetry, a movement mostly remembered as a brief stop along the way to Romanticism when otherwise dull Neoclassicists took to the cemeteries. (It was a genre tailor-made for Edward Young. One hopes he kept his skull in storage for just such an occasion.) But while the gloomy backdrop was new, the poetry itself was rather conservative. Night Thoughts is a 10,000-line meditation on death, written in blank verse, draped in classical allusion and decorated with righteous Christian thoughts about resurrection. There’s little in the way of narrative, so the dozen-or-so lines in which Young describes sneaking into the cemetery are surprisingly cinematic—so much so that they inspired a popular painting by Pierre-Auguste Vafflard. In the painting, Young looks like a different man entirely; he’s gaunt but strong, pallid in the moonlight with fashionably tousled hair, not a powdered wig in sight. His arms clasp around a woman so stiff and pale she seems carved out of marble. In this painting, it’s easy to see why, from Night Thoughts on, Young was no longer considered second-rate, no longer a punch line: A dead woman lent him the gravitas he craved; she revamped his image and secured his place in literary history. No wonder, then, that José Cadalso wanted to imitate Young’s style nearly fifty years later.

For all Cadalso’s claims of imitation, there’s a glaring difference between his Lugubrious Nights and Young’s Night Thoughts, even if you overlook the difference between Young’s blank-verse meditation and Cadalso’s plot-driven prose: Cadalso’s fictional proxy, Tediato, doesn’t come to the cemetery to bury his unnamed lover—he comes ready to dig her up. And while Young keeps his “sacrilege pious,” Tediato’s post-exhumation plans start with taking the corpse to bed. At the end of Cadalso’s first night (borrowing Young’s structural device), Tediato takes a moment to address his lover’s body, which remains buried despite his efforts:

“Oh you, image now of what I shall be shortly; soon I shall return to your tomb, I will take you home with me, you will rest on a bed next to mine; my body will die next to yours, adored cadaver. Expiring I will set my domicile on fire, and you and I will turn into ashes in the midst of those of the house.”

People immediately found it suspicious that Cadalso, a man grieving the sudden death of his girlfriend, would write a poem that included such a bizarrely specific plan: dig up his lover, get the corpse into bed, commit suicide, then somehow self-cremate by setting the house on fire. He had to be thinking of María Ignacia when he wrote that passage. So when Cadalso referred to his poem’s “true part” in a letter to a friend, it seemed like he confessed to what many assumed to be true: That, fueled by grief, or more likely a heroic amount of booze, Cadalso broke into the cemetery at St. Sebastián’s and tried to exhume María Ignacia’s corpse.

Given these scandalous rumors surrounding Lugubrious Nights, it’s doubtful the Reverend Dr. Young would have been flattered to find his name on the cover of Cadalso’s poem. Still, he might have been sympathetic to the kind of grief Cadalso described.

In 1740, Young’s son-in-law, wife, and closest friend all died within a year. These misfortunes came on top of the death of his stepdaughter Elizabeth four years earlier; the eighteen-year-old newlywed died of consumption in Lyon on her way to Nice. Like Young, Elizabeth was Protestant, so the nearby Catholic cemeteries refused to bury her in their consecrated ground. Young was outraged:

“Denied the charity of dust to spread

O’er dust! a charity their dogs enjoy.”

This was his character’s justification for gatecrashing the cemetery in Night Thoughts, the implication being that the Catholic cemetery had rejected Narcissa’s Protestant body. To anyone who knew Young, there was no doubt the mysterious Narcissa was a pseudonym for Elizabeth.

But in Young’s retelling of Elizabeth’s burial, he changed another identifying detail: the city of Lyon became Montpelier. Here, his poetic license began to blur with the truth: Gossip spread about a Protestant poet forced to sneak his daughter’s body into a Catholic cemetery in France; sympathetic Protestants even made pilgrimages to Montpelier, attempting to locate and collect dirt from poor Narcissa’s grave.

This misreading of Night Thoughts highlights one last similarity between Edward Young and José Cadalso, something beyond poetry, grief, dead women, and rumors of busted cemetery locks—that is, despite all the lingering aspersions, neither story is true. Or rather, Elizabeth and María Iganacia’s deaths are real, but neither poet ever snuck into a cemetery.

Truth Told Slant

Elizabeth was, in fact, buried in Lyon, in the general hospital’s Protestant cemetery. Her tomb was there all along, even as misguided Englishmen searched Montpelier for her unmarked grave. While Young’s fans focused on the wrong city, the hospital converted the cemetery into a medicinal garden. Leaves grew over Elizabeth’s headstone, weather softened the Latin engraving, and the real Narcissa was forgotten. This matter wasn’t corrected until her grave was rediscovered by bibliophile and dilettante-historian Alfred de Terrebasse in 1832, much to the relief of the long-maligned French Catholics.

Elizabeth’s burial was modest, but it certainly wasn’t surreptitious, since it was in a graveyard set aside for Protestants. Edward Young, however, had a real, if less macho, reason for remembering Elizabeth’s burial as particularly harrowing: He was charged an unconscionable 729 livres for her funeral and grave, an amount that would still be out of line one hundred years later. (For comparison’s sake, his first play, Busiris, was considered a success, and earned 84 livres.) Though he bristled at the cost, this petty complaint disappeared in Night Thoughts: In the poetic version of Elizabeth’s burial, rather than paint himself as an ineffectual, grieving stepfather stuck with the bill, he makes himself an 18th-century Walter White, a man who took matters into his own hands and did wrong only in order to do right.

As for María Ignacia Ibáñez, there are still those who believe the church of St. Sebastián got rid of its cemetery as a response to Cadalso’s impromptu exhumation. You can hear that rumor repeated as fact if you listen to tour groups pass the church today. But the truth is that most parish cemeteries halted burials in the 19th century due to Napoleon’s public health codes. Corpses—not only in Madrid but in cities across Europe—were banished to sprawling modern cemeteries on the outskirts of town. Later, as cities grew, many of the small, decommissioned churchyard cemeteries relocated their remaining bodies so the land could be repurposed. Somewhere in this shuffling of graves, María Ignacia vanished.

One of the last published mentions of St. Sebastián’s cemetery comes from Curzio Malaparte’s account of a night in 1934. He wrote that a group of drunk men walked past the soon-to-be-demolished cemetery to gawk at the corpses lying aboveground in open coffins, waiting to be moved to a mass grave in one of the newer suburban cemeteries. According to Malaparte, an author in this group dedicated a poem to the corpse of a young woman he saw that night. It wasn’t María Ignacia, but in theory, she should have been there, dug up for good this time, though it seems too much to ask to find her there, the muse for yet another poet. It was as if Cadalso had already consumed her, bones and all, leaving nothing for this last ghoulish party to pick through.

Elizabeth and María Ignacia’s epilogues are worth documenting if for no other reason than literary critics in the past have been too credulous with both writers—too eager to mistake the emotional truth of poetry for the facts of history. But the fictional autobiographies in Night Thoughts and Lugubrious Nights are still worthy of consideration. Even if they can’t give us the facts and just the facts, they can tell us how Young and Cadalso’s minds worked, what they valued and how they imagined themselves to be.

Young’s logic for burying Elizabeth is immediately understandable. The stand-in he wrote for himself is devout, serious, and smart enough to conceal his emotions behind opaque references to the ancient Greeks. His goal, to bury the dead, even has a classical echo. He is Antigone, bravely risking his own honor to properly bury his stepdaughter.

And then there’s Cadalso with his Romantic ideas about digging up his lover and dragging her body away so he can die by her side. What would possess a man of the Enlightenment to write himself as so utterly unhinged? More to the point, what would make so many other writers follow suit? The fate of María Ignacia’s corpse became a hallmark of Romantic literature: the dead woman is never simply a person to be mourned and forgotten (like Elizabeth). Rather, she is fully objectified and consumed. Her body becomes a source of constant craving, an impossible possession, a grieving man’s objet petit a. Look around and you’ll see her in Annabel Lee, the first Mrs. de Winter, and Laura Palmer. There was something bigger at work in the Romantic movement as a whole as it spread through continental Europe to England and back again—something that would have influenced Cadalso in Spain, but not Young in England.

A hypothesis: that influence is Rome. It’s in the name of the movement, as it is in the phrase Romance language. But perhaps the most accurate way to describe it is Romish, a pejorative Protestant term for all things Catholic. Later Romantics became fascinated with Rome and its ghastlier Catholic rituals. Chateaubriand and Stendhal wrote of barefoot confraternity members carrying corpses through the streets by candlelight. A letter from Lord Byron described masked Catholic priests with black crucifixes who presided over a public execution (which he watched through his opera glasses). Nathanial Hawthorne shuddered at the mummified Capuchin friars on Via Veneto, and Goethe marveled at a mass for the dead on All Soul’s Day. But before these writers traveled abroad to experience this culture shock, Cadalso tapped into it in his native Catholic Madrid. There, he could hardly avoid the influence of Rome—especially when those Romish rituals involved digging someone up.

Tour Bus to the River Styx

Cadalso’s Catholic impulses are more easily understood if you leave the cemetery at St. Sebastián’s and take a bus just outside Madrid’s city limits to El Escorial, the royal monastery devoted to death. There, you’ll find two rooms that clarify his motive: the putridero and the relicario.

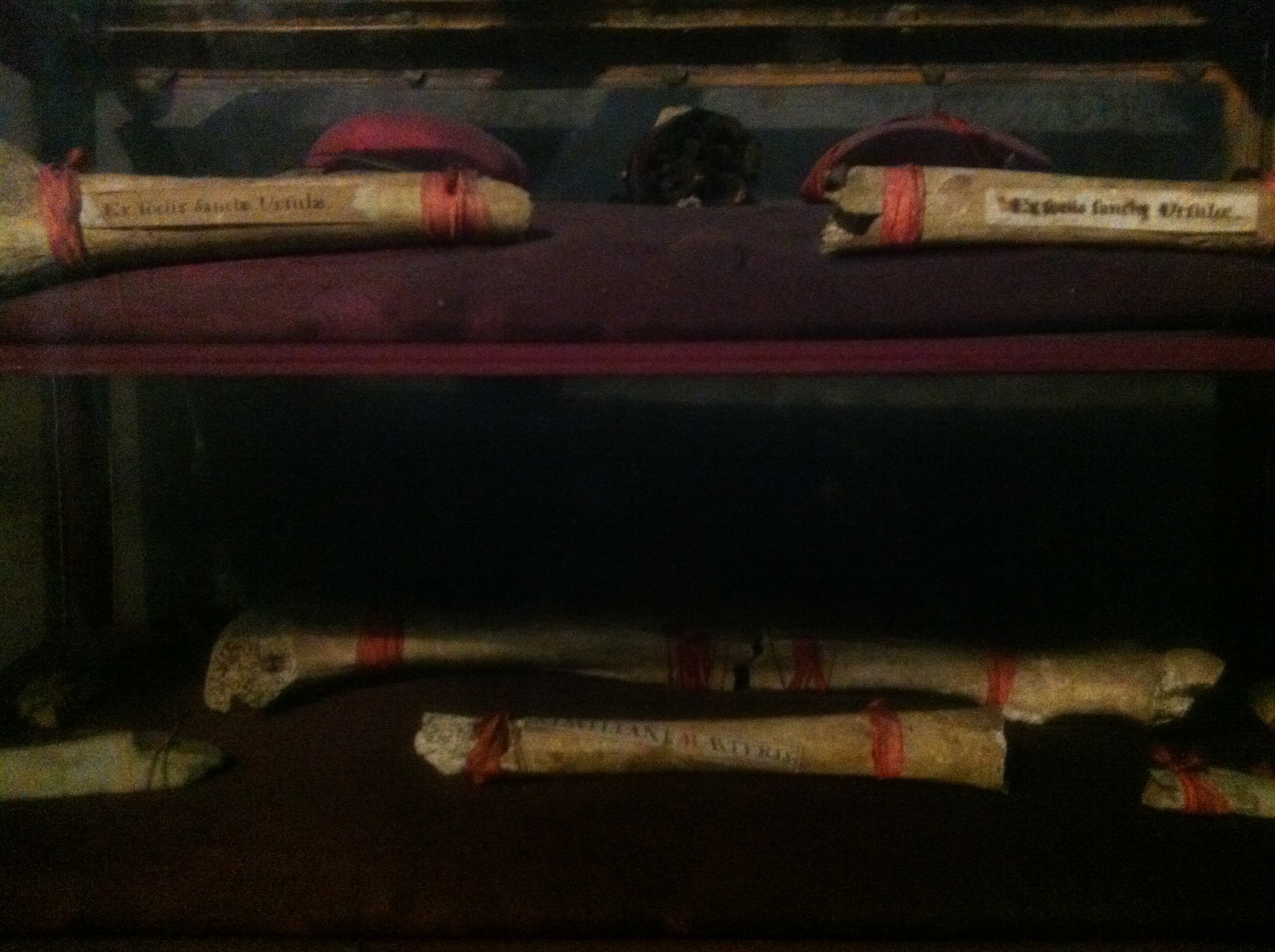

There are thousands of people in the relicario, but it’s difficult to see them that way. They aren’t really people anymore—they’re objects: 144 heads, 306 arms and legs. All told, more than 7,000 holy relics, the parts and pieces of Catholic saints collected by King Philip II, are stored here.

Philip II pursued saints’ relics with the same zeal as the original relic collector—the Empress Helena. She scrounged the Holy Land in the 4th century in search of dubious pieces of the passion, sending crosses, thorns, and nails back home to her imperial palace in Rome. But Philip II wasn’t one for archaeological digs. Instead, he frantically asked every parish in Spain if their relics were displayed prominently enough, if the displays were opulent enough, and if enough people were coming to see them—if not, he offered them a new home in his jealously guarded collection at El Escorial. He kissed the relics, prayed with them, and laid them all over his ailing body—a saint’s arm on his arm, a kneecap on his kneecap. It was said that on his deathbed, the only thing that would snap him back to consciousness was to casually mention someone else touching his beloved relics.

In Lugubrious Nights, Tediato refers to his lover’s corpse as a “sad relic.” Like the precious bones in the relicario, she’s no longer a person to him, but a missing piece of his collection, a sacred object to be rescued from the isolation of the grave. In this context, there is no higher honor than to be hoarded and venerated; to be objectified, to lose your humanity, is to become something more than human, not less. In Cadalso’s world, it’s an honor befitting a saint—or royalty.

The secular version of El Escorial’s relicario is the putridero. It’s a secret room behind the royal crypt. Only monks and royal corpses are allowed inside. When a king or queen who has birthed a king dies, this is the room where the first of two burials takes place.

Traditionally, many Catholics in Italy are buried twice: once when they cease to live and again when their bodies cease decaying. This tradition was exported to Spain (via the Spanish-ruled Kingdom of Naples) in the form of El Escorial’s putridero, but here, as is often the case with imports, it has a certain cachet that’s absent in its home country. In Italy, the bodies of monks or nuns are often left to rot on strainer-seats or covered with a few inches of dirt in public crypts, but in Spain the royal bodies are hidden away in wooden caskets. During this period, the first death, the body is dead but lacks the stillness death brings. It purges fluid. It sheds flesh. It’s unpleasant. At the same time, the body’s soul is thought to be in purgatory, an equally unpleasant and liminal place. Purgatory is where souls are purified in a metaphysical lake of fire before being admitted into heaven.

The Church isn’t clear about whether all heaven-bound souls go to purgatory, or if they do, for how long. No one can seem to translate time spent in the afterlife into the units of time used in our world. This is why it falls to the organic timeline of decay, a period of experienced instead of measured time—kairos instead of chronos, as the ancient Greeks would say. As long as the body is purging flesh, the soul is thought to be purging sin. When only a clean, white skeleton is left, the soul is considered at peace in heaven. That’s when the monks at the royal monastery move the remains into one of the identical marble caskets in the pantheon: a secular kind of reliquary.

Disturbing a grave in this context is a privilege, so somewhere in Cadalso’s Catholic subconscious, he may have imagined digging up María Ignacia as a way to honor her like a queen or saint. Drawing on the ritual of double-burial even explains his character Tediato’s needlessly difficult plan to commit suicide and somehow burn down his house afterwards. To mirror the Catholic ritual, the deaths must happen in that order. The body dies first; finality and peace only come with the second death, after the purgatorial fire.

These ideas were repellant to Protestant reformers, of course, and contrary to the burial customs Edward Young practiced. Young never considered the physical realities of Narcissa’s corpse, even as he described her burial; he had no use for corporeal Catholic rituals. Instead, he consoled himself with thoughts of the Day of Judgment yet to come. To linger on the thought of her body would be excessively morbid and distasteful to him.

A Cold and Drowsy Humor

Cadalso’s references to double-burial and relic veneration set his Romish Romantic poetry apart from Young’s Protestant Graveyard poetry. But Cadalso wasn’t the first Spanish writer to exploit Catholicism’s porous boundary between the living and dead, especially when the corpse in question belonged to a beautiful young woman.

As the sign on St. Sebastián’s advertises, there was a much more famous tomb in the cemetery where María Ignacia was laid to rest: the playwright and poet Lope de Vega was buried there in 1635. (Though his tomb is now inside the church—avoiding a move to a mass grave is one perk of being famous.) He was interested in dead women, too, though no one ever accused him of consorting with one.

In de Vega’s play La Difunta Pleiteada (The Deceased was Petitioned), a Sicilian girl’s father arranges her marriage to a man other than her lover, which causes the girl to succumb to an antiquated lady-in-love-psychosis and die. But before her tomb is sealed up, her lover sneaks into the church where she’s laid out and steals a cold embrace. Instantly she’s resurrected, though this leads to a protracted lawsuit between the two men who want to marry her.

Though both The Deceased was Petitioned and Lugubrious Nights deal in dead women, the former is rather quaint compared to the latter. In de Vega’s version, the girl’s resurrection seems to have a halo sketched around it, a hopeful shine that only a true believer would include. De Vega was, in fact, a devout Catholic. He believed in the supernatural powers of the Church and often re-told miraculous stories that were passed down to him through ballads and folklore. For this reason, de Vega is often compared to his contemporary, Shakespeare, since both writers used plots from existing sources. But de Vega’s writings are also indebted to hagiography. Like the writers who recorded the lives of the saints, he was more interested in truthfully documenting the wonder of the world than the reality of it. These priorities were understood during his time, but today they strike most readers as false. Modern audiences have yet to untangle themselves from the insistence on psychological realism and the concept of authenticity the Romantics demanded—which is exactly what Cadalso offered in addition to his fascination with Catholic rituals.

There is a pervasive, if morbid honesty in Lugubrious Nights, particularly in Cadalso’s willingness to record his own dark thoughts and his affinity for observing nature—even to the point of imagining maggots in the body of his lover. In the poem, Tediato exclaims:

“Into these worms, oh! Into these your flesh has been turned! From your once beautiful eyes these sickening creatures have been engendered! Your hair, which in the height of my passion I called a thousand times not only more blond but more precious than gold, has produced this rot. Your white hands, your loving lips have turned into matter and decay!”

But perhaps Cadalso’s honesty is most apparent, and most sympathetic, in the way he paints Tediato as someone drawn to the traditions of the Church long after his faith in God has been irrevocably shaken by rationalism.

This rationalism was noted by none other than the Spanish Inquisition in Córdoba, who banned Lugubrious Nights in 1819. They objected to Tediato’s planned suicide and the fact that he never fears hell; Tediato’s omission of the Catholic afterlife becomes particularly obvious when he rejects the idea of a secular afterlife altogether. When his gravedigger-accomplice retreats, fearing ghosts in the cemetery, Tediato suddenly sounds like a modern skeptic:

“What’s frightening you is your very own shadow together with mine. They are produced by the position of our bodies with respect to that lamp.”

In other words, death is not just real to him, but final. Tediato (and therefore Cadalso) stared into the void without a supernatural glimmer of hope.

As Mario Praz wrote in his book The Romantic Agony, a Romantic is interested in the natural monstrosities and aberrations of our world. And like a true Romantic, Cadalso was only interested in the observable—the natural and psychological aspects of death instead of the supernatural. A good Catholic in his day would fear an eternity in hell for that, but perhaps Cadalso was punished in another way. Unlike more devout writers like Lope de Vega or even Edward Young, Cadalso’s agnostic grief continues to ring true in the modern world—so much that people have mistaken it for literal truth for over two centuries now.

A Gentleman’s Stiff

The subtle nihilism of Lugubrious Nights feels modern, but there’s one detail that would certainly change if the story were told today: Cadalso is never clear if Tediato succeeds in digging up his lover’s body. On the first night he runs out of time, on the second he’s waylaid by the police. The third ends enigmatically when he meets his gravedigger-accomplice one last time and says:

“You will contribute more to my happiness with that pick, that mattock… vile instruments in the minds of others… venerable in mine… Let’s go friend, let’s go.”

That’s the end, ellipses and all. There’s no climax. No one witnesses the consummation of Tediato’s nightmarish plan nor his anguished failure.

The fact is, Cadalso can’t give us what we’re looking for. His outlook was bleak enough to imply that Tediato’s happiness could only be found with the gravedigger’s tools—a pick and a mattock—but he can’t quite bring himself to elaborate. Like later Romantics, he concerns himself with longing but not satisfaction. Satisfaction in this case would require the reader to want to see the last grim scene between Tediato and his lover’s corpse. And that desire could be called sadistic. Those whose tastes lean in that direction only need to look as far as the most obvious source—the Marquis de Sade, who couldn’t resist rewriting de Vega and Young and Cadalso’s tale one more time in Juliette. But unlike Romantic Cadalso, he could do so with the promise of satisfaction, no matter how perverse. And so the dead woman shifts again: from pious saint to romantic obsession to object of decadence.

The Marquis borrowed his setting from Lope de Vega: an Italian church where a shrouded young woman awaits burial. From Edward Young he borrowed the character of the bereaved father. Then, in his own inimitable style, he combined that character with José Cadalso’s distraught lover. This man, Cordelli, bribes the gravedigger for some time alone in the church before his daughter’s vault is sealed.

Once he’s alone, Cordelli incestuously embraces the girl, though she doesn’t revive like she would in one of Lope de Vega’s plays. (Sadism and decadence, being vagaries of Romanticism, require a certain degree of naturalism.) The permanence of the girl’s death is for the best anyhow: The scene devolves into a long and bloody orgy, the details of which can be found around page 1,046. There is no passage to reasonably quote.

The novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans once said that sadism is the bastard of Catholicism—a direct descendent, but an embarrassing byproduct of its ecstasies. Cadalso may have preferred to end his poem before creating such an abomination, but Catholicism kept influencing writers long after him, eventually ushering in the likes of de Sade and the Decadents who were happy to pick up where he left off. Like Cadalso, they were inspired by the martyrs and their objectified bodies in crystal caskets—they just also had a predilection for the tortures that put them there in the first place.

There’s no turning back in this evolving story of the beautiful dead girl. The literary tradition that bubbles up from beneath that funereal flower shop at St. Sebastián’s continues today. Like Tediato, modern audiences still find happiness in picks and mattocks, and have access to de Sade’s racks and knives as well. We put them into constant use in the latest gritty cable crime-drama, providing the latest dead girl with her arched back, rolled eyes, clenched fists, and unwilling willingness. It’s a work-around. It provides a one-sided kind of sex—a necessity, because Catholicism’s persistent influence ensures we still love virgin-martyrs the very best. Like de Vega, Cadalso, Young, and de Sade, we’re still hauling out their bodies, filling up our reliquaries, and making new adored cadavers.

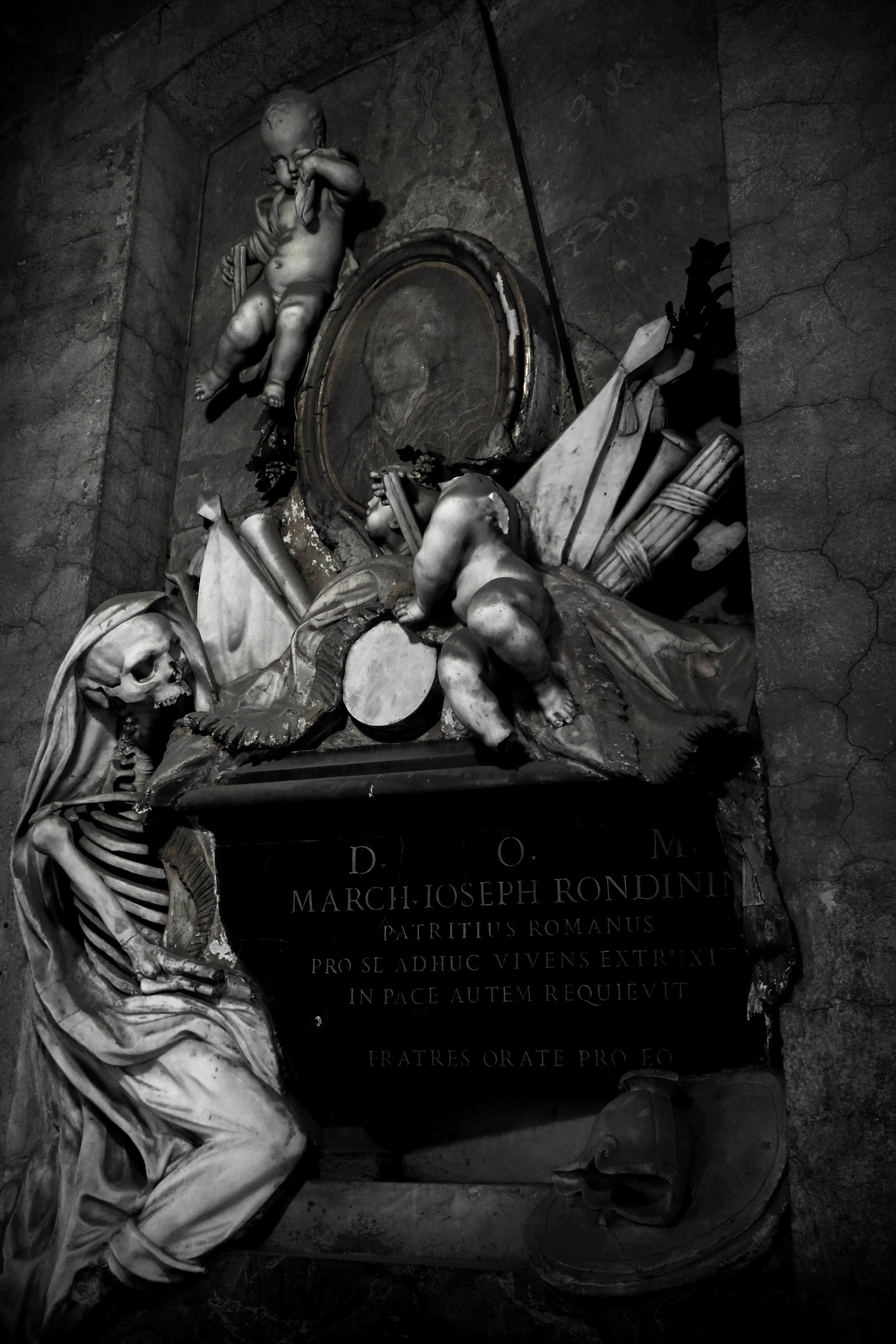

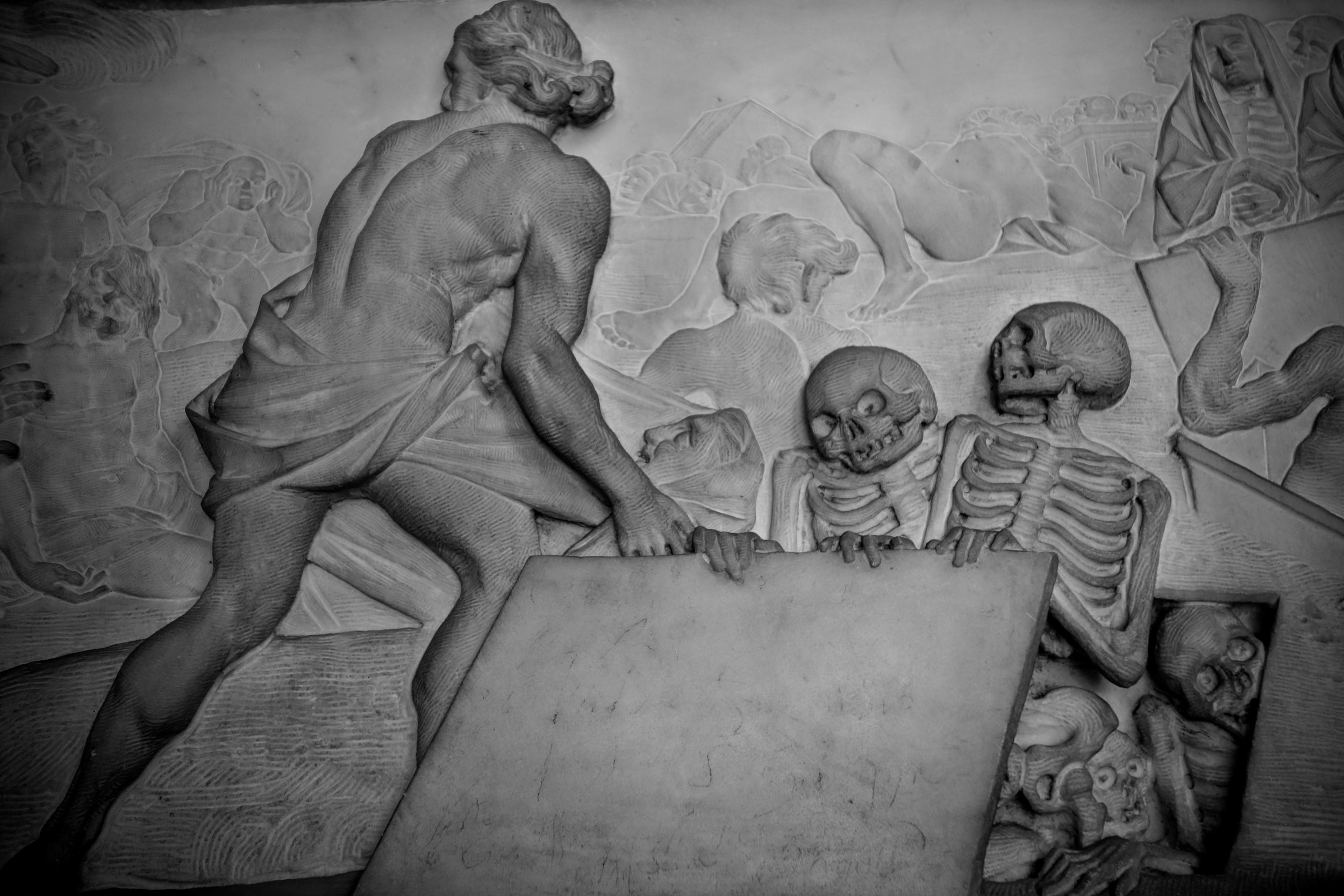

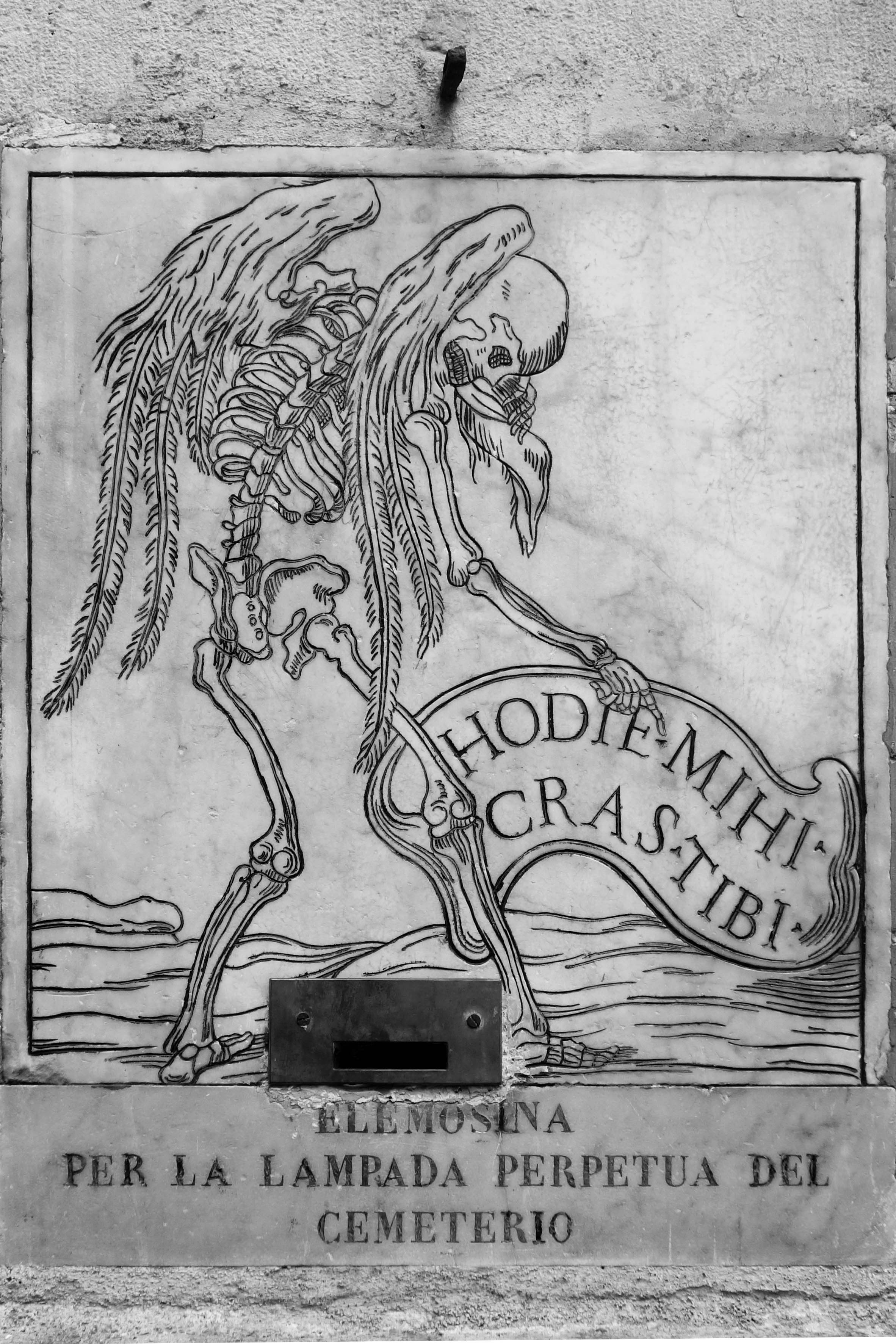

The Sculptural Skeletons of Rome: As Seen in Slate

Originally published on Slate.

The dead are everywhere in the churches of Rome. Their tombs line the walls and dominate whole side chapels. Visit enough of them and you’ll come to expect the loose wiggle and hollow thunk of the marble slabs shifting beneath your feet that signal you’ve walked over a grave. If you imagine what’s just beyond every surface, the churches become mega-necropoli, Tokyos made of tombs instead of hotel rooms.

Unlike the relics of the saints, the entombed bodies of clergy and parishioners are largely hidden from the public, but the Baroque skulls and life-sized marble skeletons won’t let you forget they’re there. They speak to you. But as David Sedaris noted in When You Are Engulfed in Flames, the skeleton has a “limited vocabulary, and says only one thing: ‘You are going to die.”

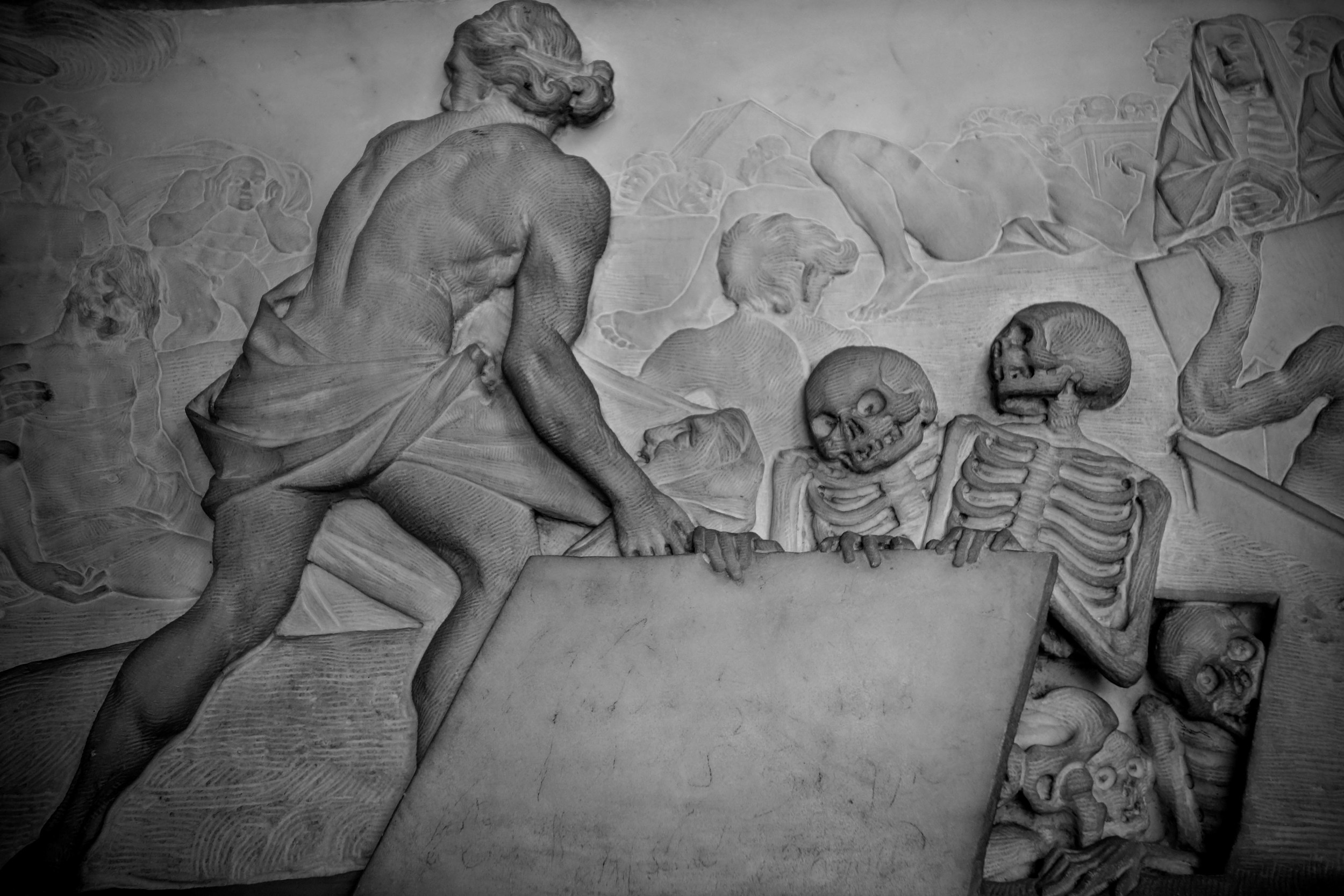

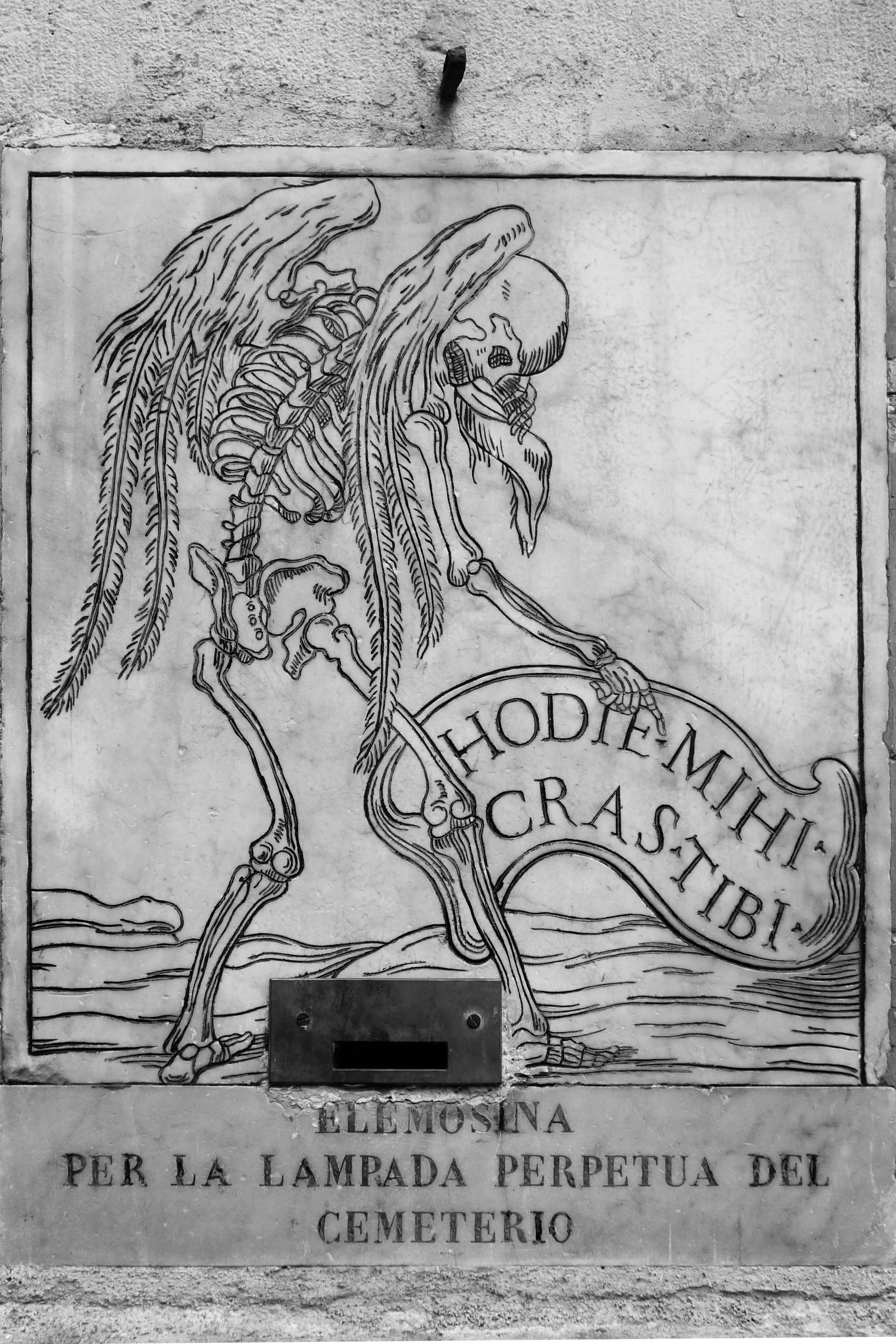

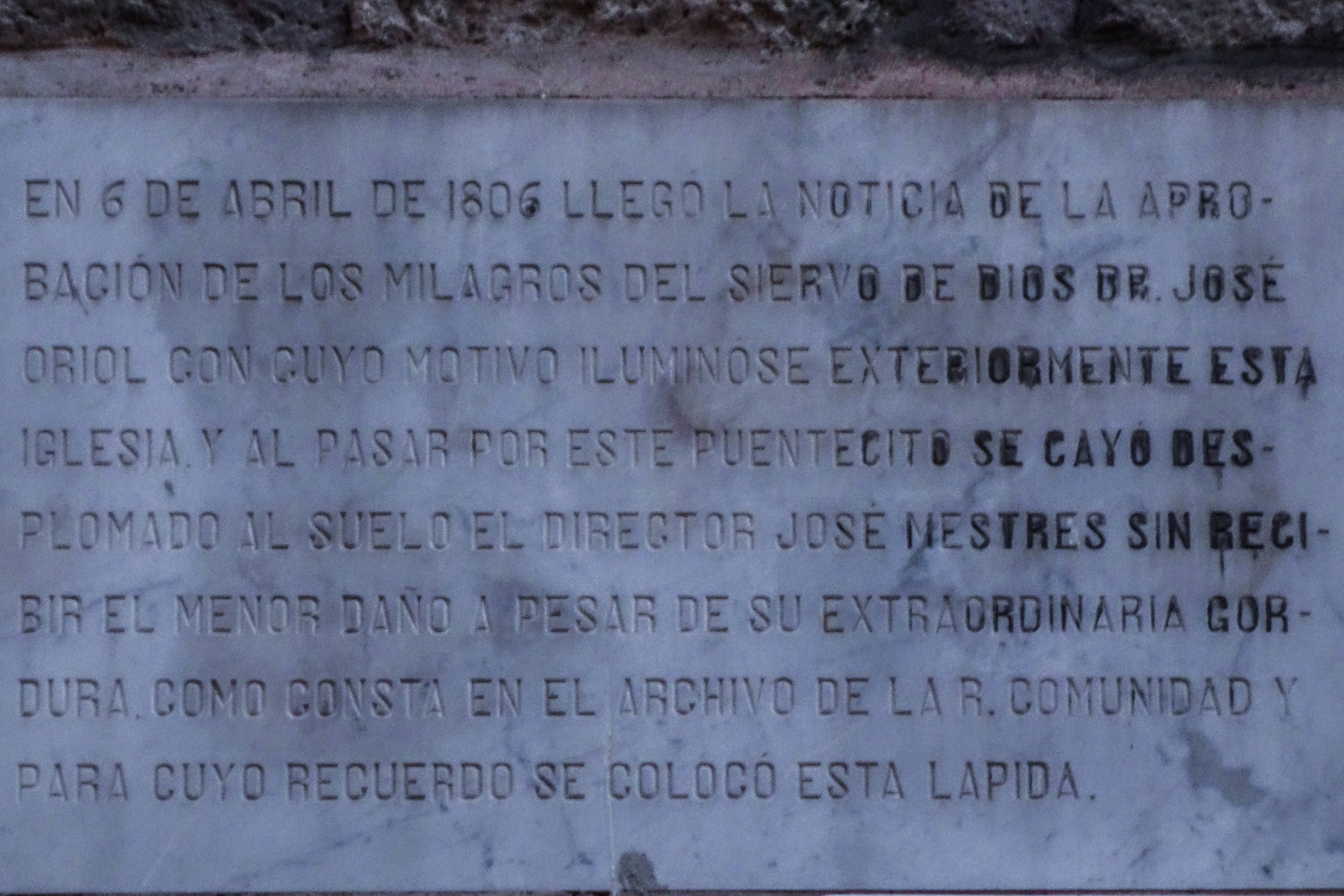

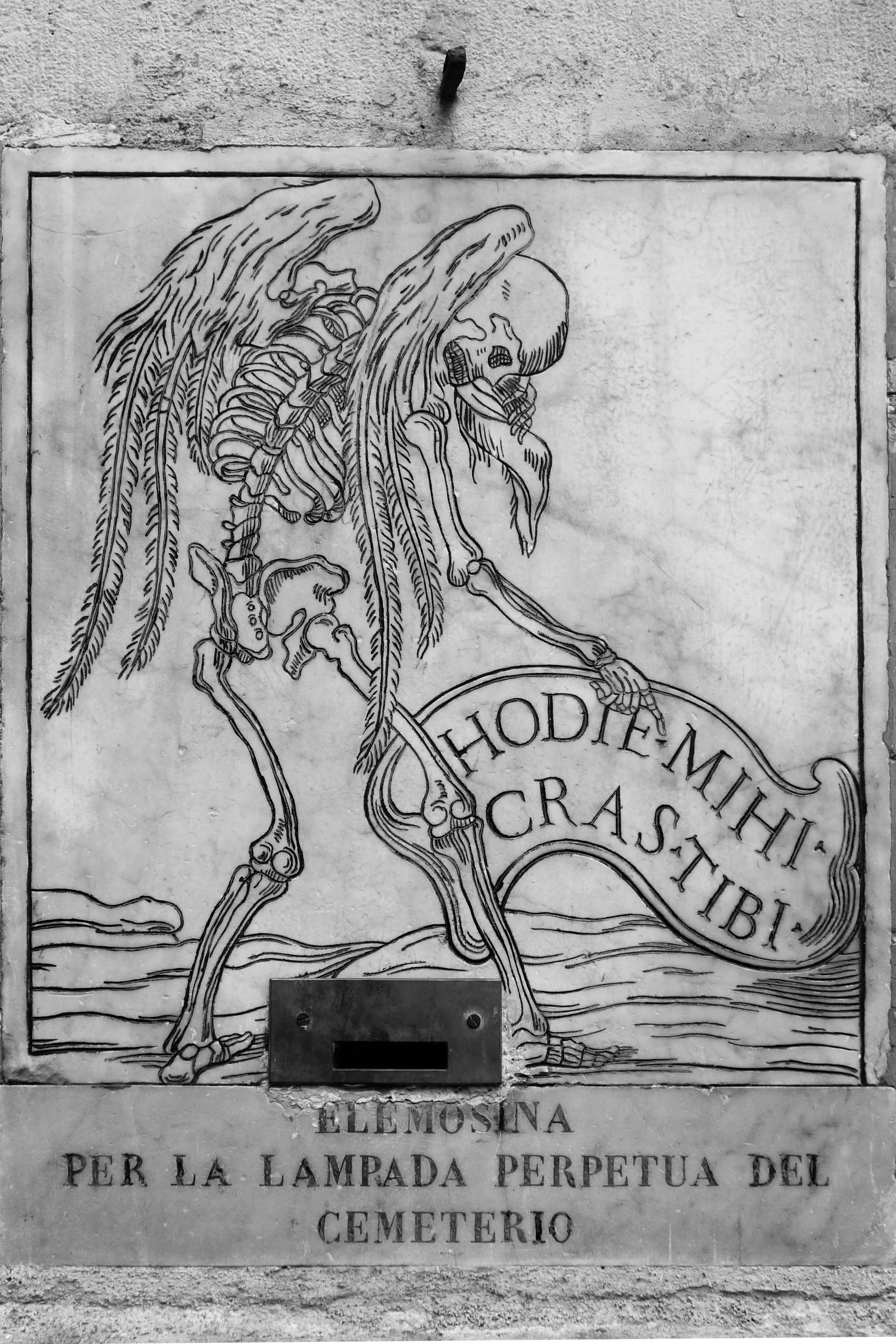

Rome’s skeletons prefer to deliver the bad news in Latin, an appropriately dead language, but even so you can’t mistake the message or the fact they’re addressing you directly. An engraved skeleton on the façade ofSanta Maria dell’Orazione e Mort unfurls a banner that reads, “Hodie mihi. Cras tibi.” “Today me. Tomorrow you,” it shrugs.

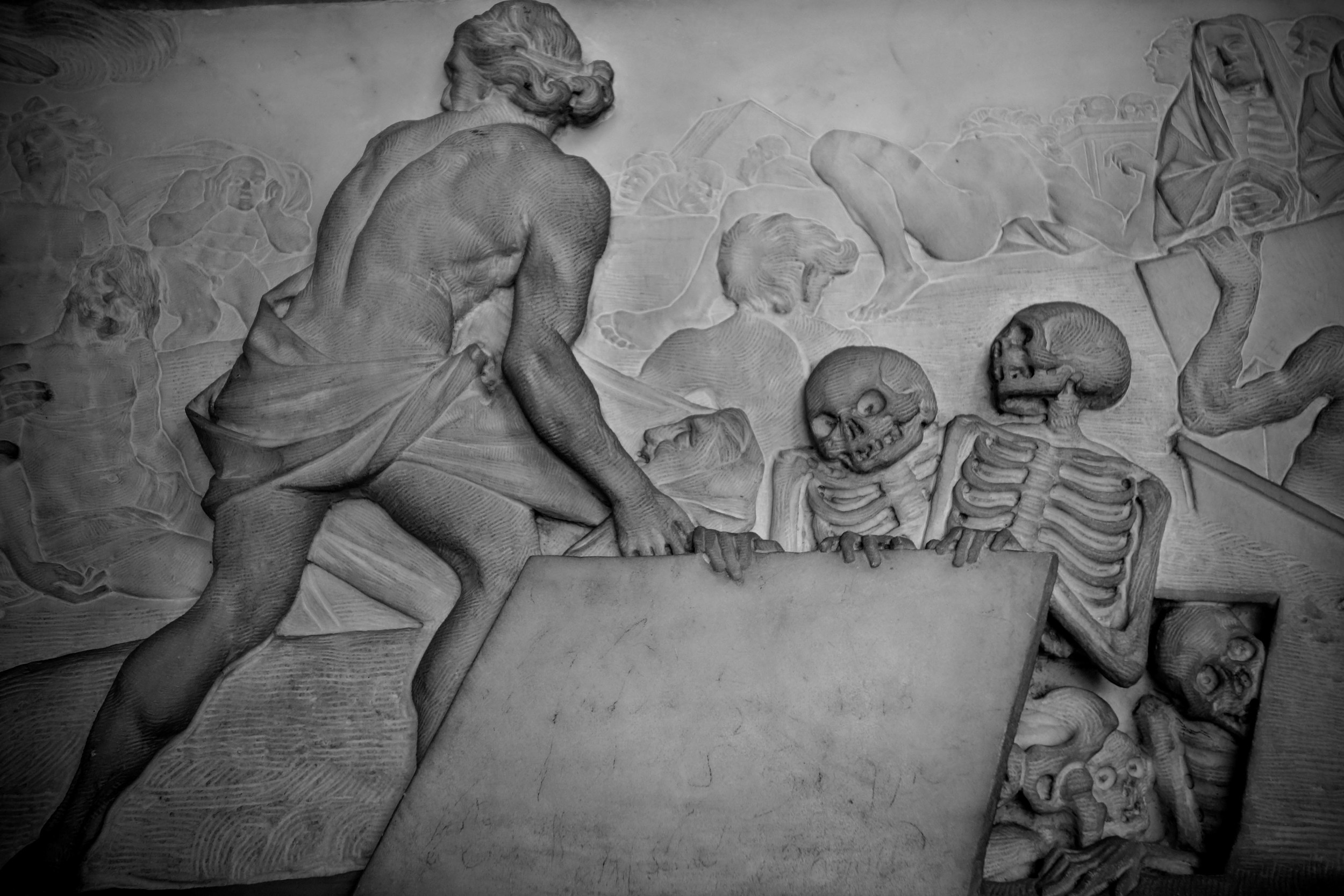

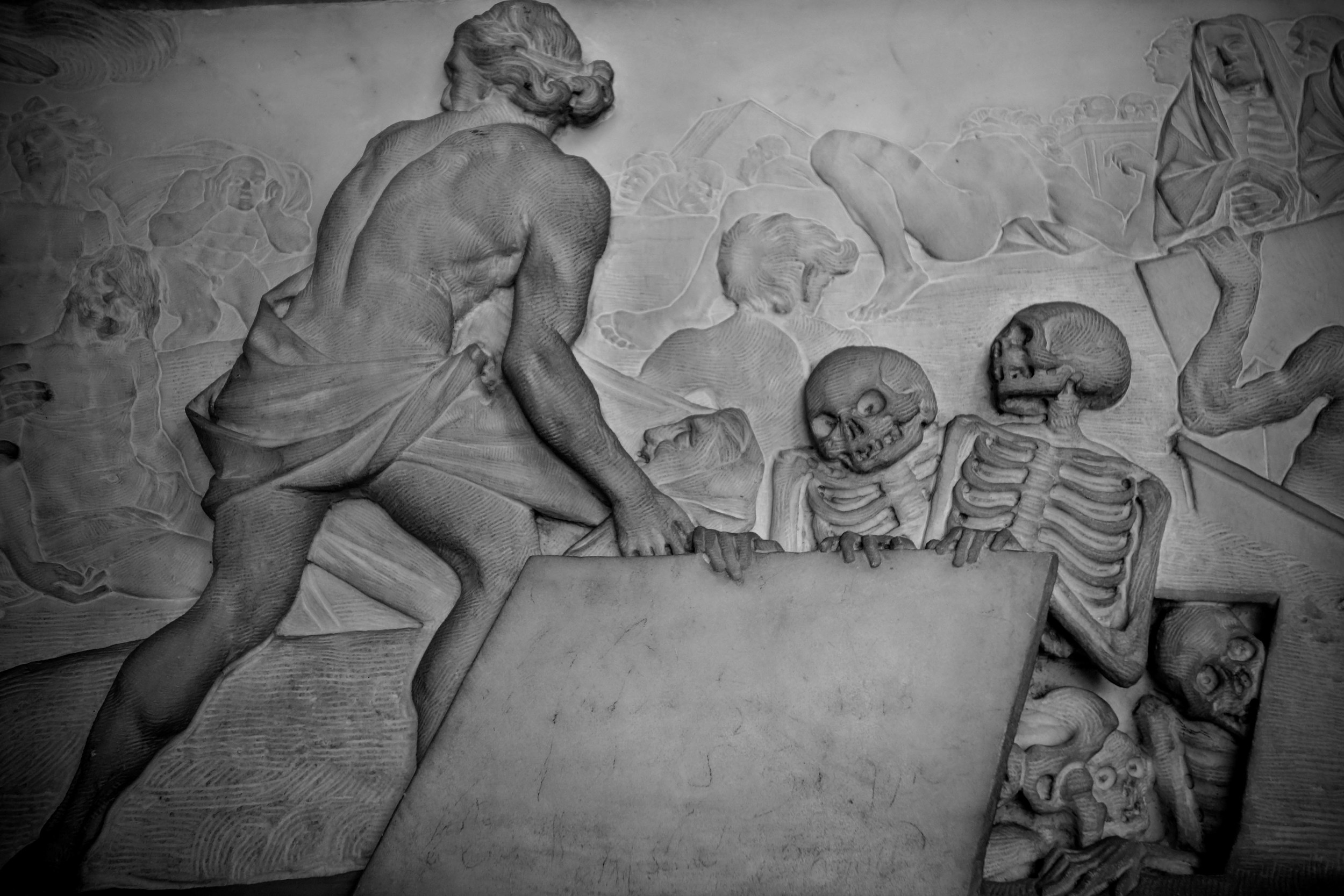

Though their message is grim, the skeletons are surprisingly lively. At San Francesco d’Assisi a Ripa Grande, they climb out from behind the artwork. At Gesù e Maria, one appears frozen in the middle of a solo danse macabre, flailing so wildly it seems to be coming apart. Even in the more staid examples, it isn’t unusual for the skull’s empty sockets to convey more emotion than busts of the living. It’s this kinetic quality that’s so arresting; life seems to bursts supernaturally from these dark corners devoted to death.

The juxtaposition is intentional. Bernini popularized the use of these unusually active skeletons, and in doing so masterfully expressed a tenant of his Catholic faith. The feathered wings signal these aren’t your average corpses. They’re complex allegories for the inescapable passage of time, and the belief that death and decomposition of the body are the first stages in the transition to everlasting life (or damnation, as the case may be). Though the skeleton may only say, “You are going to die," for some that implies, “You haven’t lived yet.”

The Neapolitan Cult of the Dead: A Profile for Virginia Commonwealth University

This profile was published as an entry in Virginia Commonwealth University's World Religions and Spirituality Project.

CULT OF THE DEAD TIMELINE

1274: Purgatory was formally accepted as Catholic doctrine and defined by the Church as “the place of purification through which souls pass on their way to paradise” at the second Council of Lyons.

1438-1443: The Council of Florence added that “the suffrages of the faithful still living were efficacious in bringing [souls in purgatory] relief from such punishment…”

1563: An additional decree concerning purgatory was passed at the Council of Trent, delineating Church-sanctioned ideas about purgatory from “those things that tend to a certain kind of curiosity or superstition, or that savor of filthy lucre”.

1476: Pope Sixtus IV confirmed that indulgences might be earned by the living for souls in purgatory, thus shortening individual souls' time there.

1616: A group of Neapolitan noblemen founded the Congrega di Purgatorio ad Arco, a group dedicated to burying the poor and praying for their souls in purgatory.

1620s: St. Robert Bellarmine taught that souls in purgatory could help the living because they are closer to God than people on Earth; however souls in purgatory cannot hear specific prayer requests.

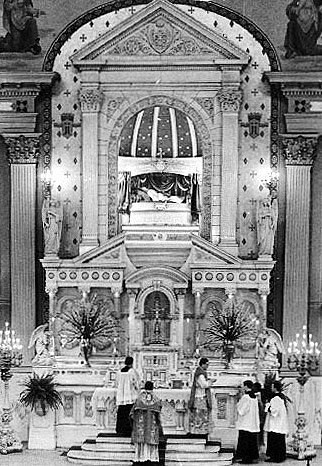

1638: The church of Santa Maria delle Anime del Purgatorio ad Arco was completed and consecrated. Below the church was a hypogeum which is used by the Congrega di Purgatorio ad Arco for burying the city's poor.

1656-1658: The Black Death, or Bubonic plague (Yersinia pestis), devastated Naples, killing roughly half of the city's inhabitants. Of the estimated 150,000 dead, many were hastily buried in pits or existing tufa caves without markers.

1780s: Neapolitan priest, St. Alphonsus Maria de' Liguori of Naples, built on St. Robert Bellarmine's teaching on purgatory. Liguori taught that God makes the prayers of the living known to souls in purgatory, which made it possible for the dead to help the living with specific matters on Earth.

1837: Victims of a cholera epidemic in Naples were buried in the mass graves around the city, including the Fontanelle cemetery.

1872: Father Gaetano Barbati sorted and catalogued the bones in the Fontanelle Cemetery with volunteers from the city, who prayed for the dead while they completed the work.

1940-1944: A number of the tufa caves used as burial grounds served as bomb shelters during World War II, giving new reason for the living to pray to the souls in purgatory, who were represented by the bones buried there.

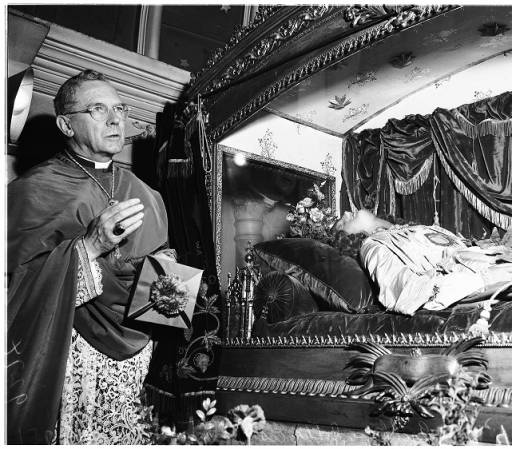

1969: Archbishop of Naples, Corrado Ursi decreed that “expressions of cult addressed to human remains” were“ arbitrary, superstitious, and therefore inadmissible.”

1969: The Fontanelle cemetery was closed, and the Cult of the Dead was suppressed.

1980: The Irpinia earthquake struck Naples, closing the church of Santa Maria delle Anime del Purgatorio ad Arco, effectively suppressing remaining activities of the Cult of the Dead.

1980s (Late): I Care Fontanelle was formed to give tours and counteract “degradation” to the Fontanelle cemetery, both the structure of the cave itself and the lingering activities of the Cult of the Dead.

1992: The church of Santa Maria delle Anime del Purgatorio ad Arco was reopened after restoration work was completed.

2000-2004: More restoration work at Fontanelle Cemetery took place.

2006: The Fontenelle Cemetery was reopened on a limited basis.

2010: The Fontenelle Cemetery was reopened full time.

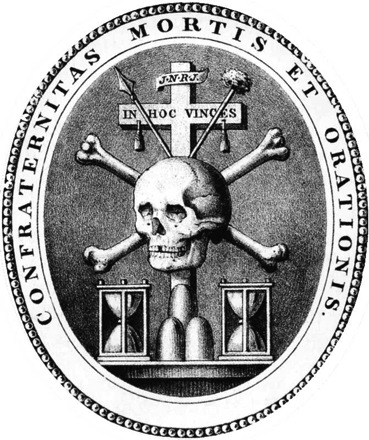

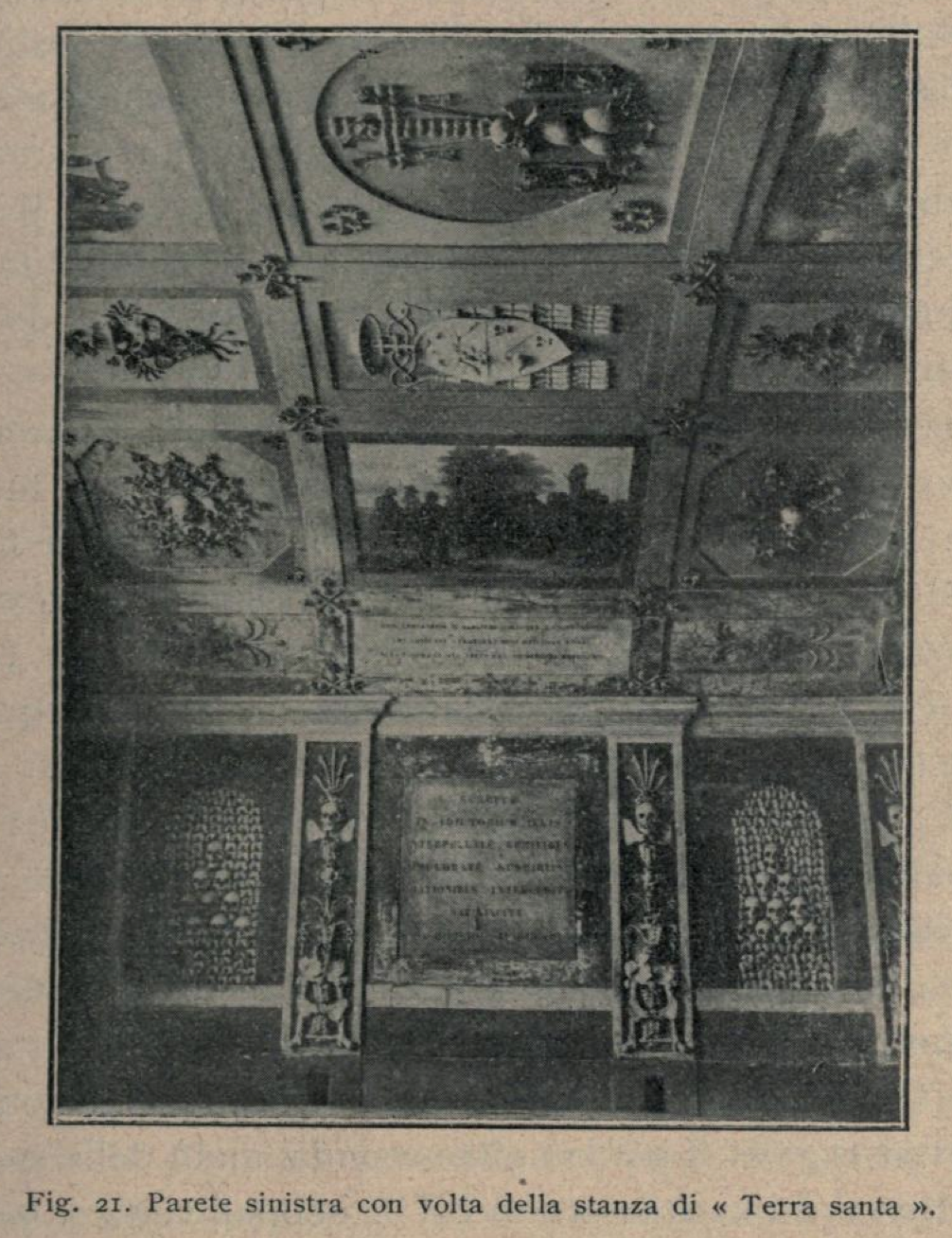

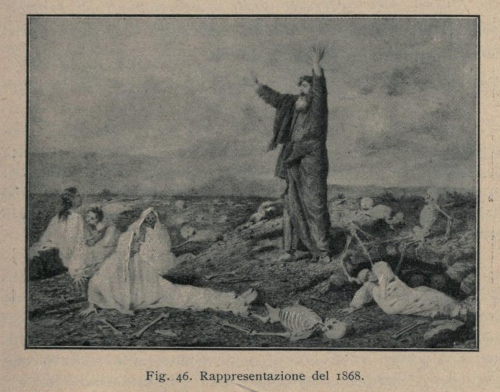

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY