Corpse Theatre

Originally published on the Morbid Anatomy Museum blog.

There’s a building that’s hard to overlook on via Giulia in Rome. It’s the one with laughing skulls over the door.

On a marble plaque at eye level, a winged skeleton holds a spent hourglass over a fresh cadaver. The plaque reads “Alms to the poor dead, which they get in the countryside.”

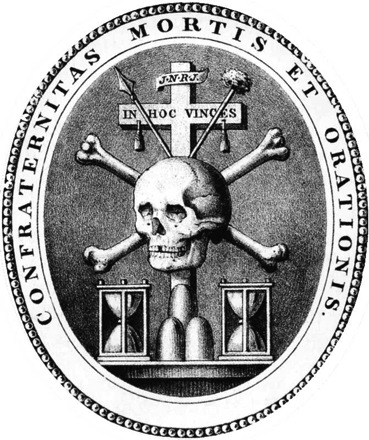

“They” is La Confraternita dell'Orazione e Morte, or the Confraternity of Prayer and Death. They were a group of Catholic laymen who buried Rome’s indigent dead and this building was their oratory.

Burying the dead is a particularly important Catholic ritual because burial is linked to the concept of purgatory. Purgatory is a place where heaven-bound souls undergo a final purification before entering heaven, but in Catholic imagery it can easily be mistaken for hell. Fire surrounds writhing nude bodies. This fire is supposed to cleanse the souls just like the grave eventually cleanses bones of rotting flesh. Appropriate, since sin and flesh are often inextricable, like in St. Paul’s letter to the Galatians where he calls everything from drunkenness to sorcery a “sin of the flesh”. After purgatory, when sin and flesh are gone for good, the clean, white bones are considered at peace and safely in heaven, which is why skeletons like the one on the façade are often shown with wings. But conversely, no burial means no peace. Though it’s not entirely orthodox, folk traditions imply that the dead can find themselves stuck in a netherworld between this world and the afterlife if they’re not given a Catholic burial.

Migrant workers in the farms outside of Rome were particularly susceptible to this fate. Malaria could kill them in the midst of their work and without family or friends to tend to them, weather and animals could ravage their corpse. The brothers in the Confraternity of Prayer and Death made the trip out to the countryside by foot and gathered these bodies year-round. It could take them four days to carry the dead back to Rome on their stretcher. They did this from 1552 to 1896. Their handwritten ledgers indicate that they picked up at least 8,600 bodies during those 344 years. If they passed a parish churchyard they would bury the workers there, but if not, they would carry them back to their oratory on via Giulia.

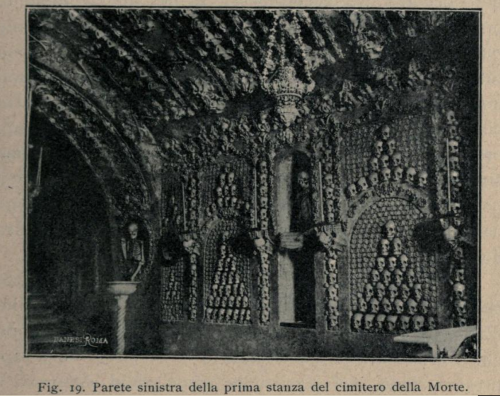

Today, the nuns who use the oratory open it for just a few hours every week while they pray for souls in purgatory. If you happen to find the church open, a donation to the sisters yields access to the crypt where you can see the lifetimes of work done by the brothers before them. Down there, you’re likely to be alone. The erratic hours mean that unlike Rome’s famous Capuchin crypt, there’s no line of nervously giggling tourists. It’s just you, the bone chandeliers, the engraved skulls, an altar full of legs and arms, and somewhat ominously, a scythe.

The overall effect is a bit ramshackle because we’re only seeing salvaged pieces of the original crypt. When the Tiber embankments were added in the late 19th century, the majority of the crypt and the order’s cemetery were destroyed. Including, unfortunately, the crypt’s theatre.

The scythe is actually nothing more than a theatrical prop, but somehow that’s even more unnerving than the real thing.

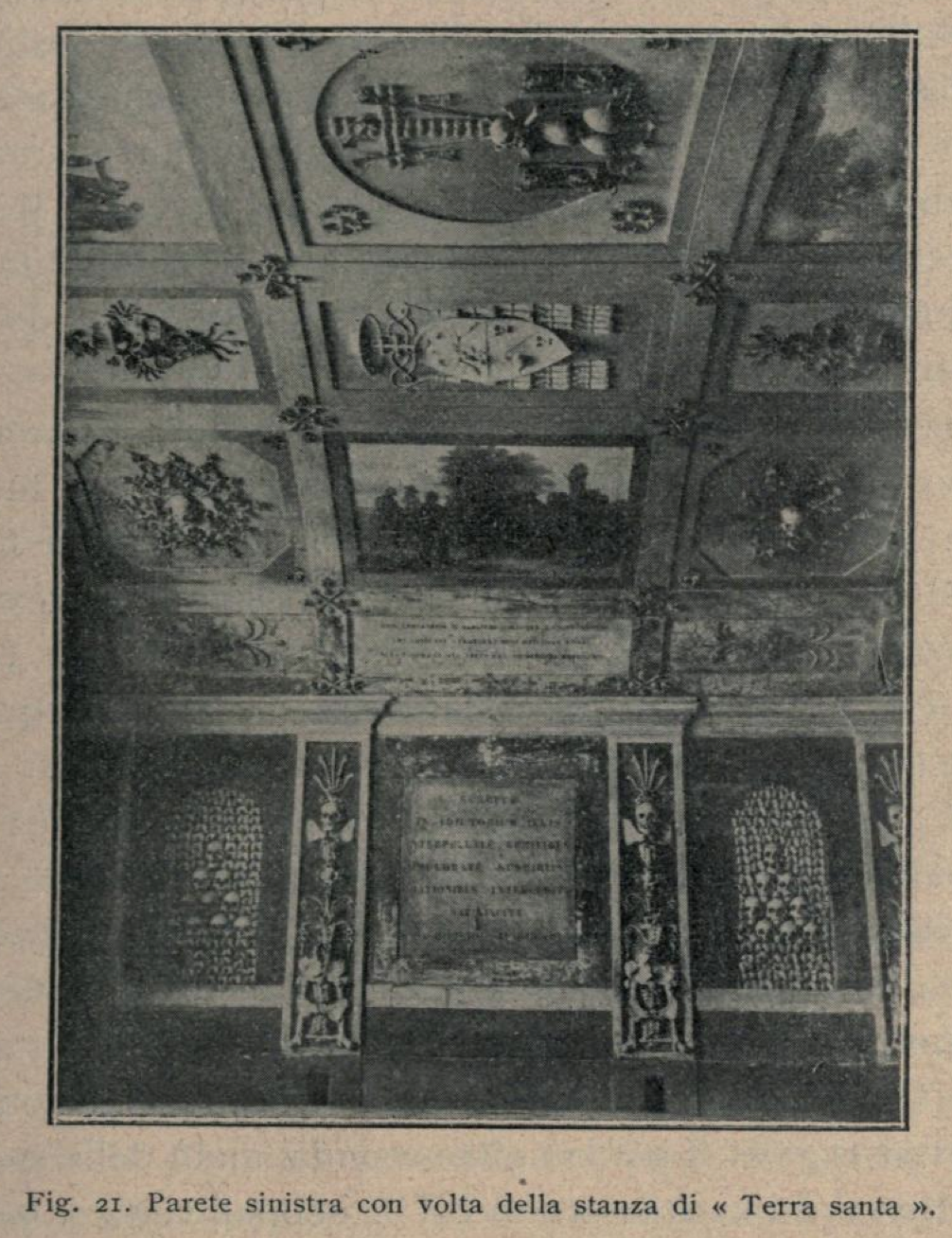

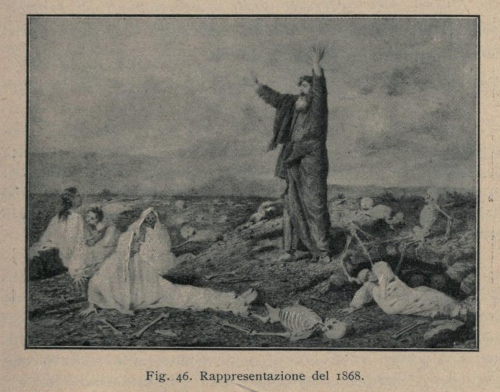

These black and white photos from the church's archives show how it once looked.

In 1763 the confraternity built a stage in their crypt. They started using the corpses they collected in tableaux staged for the public called sacred representations. If you’ve ever seen one of those Christmas manger scenes where a real Baby Jesus is depicted more or less in a petting zoo, you’ve seen a sacred representation. The only difference was the confraternity was using dead people, not farm animals.

They staged a sacred representation every year for the week following All Souls Day. It started simply with “The Burial of Jacob”. A few flat paintings were used as scenery and a corpse played Jacob’s corpse. Specific death scenes were always popular, The death of Judith, Jezebel, and St. Paul were all staged along with a few more universal tableaux, like “the allegory that we all must die”.

Every year the productions became more elaborate. By 1790 they had life-sized wax figures playing the roles of the living, dressed in costumes designed for the occasion. In 1802 when they staged “The Mountain of Purgatory” they built a mountain surrounded by candelabra. The figure of Justice was perched up high holding scales and a sword. Beneath him you could see souls in the flames of purgatory. One lucky soul was shown being lifted by a cherub and taken up to heaven. When staged with actual dead people, it’s hard to make a scene like this any more literal. The sacred representations were seen as a useful teaching tool that transcended language and literacy barriers.

Other churches in Rome like Santa Maria in Trastevere and the now deconsecrated cemetery chapel of the Lateran put on similar, though less elaborate tableaux. But another place that rivaled the Baroque stagecraft of Santa Maria dell'Orazione e Morte was the hospital just across the Tiber—Santo Spirito.

If you visit Santo Spirito today, you won’t find a trace of the sacred representations, but there are eyewitness accounts and engravings of the shows that were performed in their graveyard starting in 1813. The confraternity there cared for the dead from the hospital and like the brothers at Santa Maria dell'Orazione e Morte, they had access to a large number of unknown or unclaimed bodies. In the days before the medicalization of death, dying at home was considered preferable and a hospital death was often a last resort for people who were poor and alone.

After sunset, theses brothers would come collect the dead from the hospital and carry them out to the cemetery. There, they would open one of the hospital’s 24 mass graves and lower in the naked body with chains. The bodies would stay there, unless they were cast in a sacred representation. A particularly noteworthy performance in 1831 depicted the final judgment. The mass graves were opened and the freshest corpses were costumed and propped up beneath a wax angel blowing the last trumpet. Fortunately, Antoine Jean-Baptiste Thomas left us with an engraving of this particular dramatization.

Starting in the early 19th century, Rome’s confraternities started to get some pushback from the pope on their use of bone and corpses. The final nail in the proverbial coffin of corpse theatre was hammered in when Rome joined unified Italy in 1870. A strict ban on burying people in convents, crypts or hospitals was enforced for the sake of public health. One of the last sacred representations was done at Santa Maria dell'Orazione e Morte in 1880. The brothers there preformed the “Vision of Ezekiel” in secret knowing their cemetery and their performances were about to become a thing of the past. In the end, their customs were as ephemeral as human flesh.

More on this topic can be found at the recent post Sacred Italian Waxworks or The Last Judgement with Real Corpses, 18th and 19th Century Italy by clicking here.