St. Ursula and Her 11,000 BFFs

The story I’m about to tell you is highly suspect. It is so suspect that even the Church admits it’s suspect and removed St. Ursula’s feast day from the calendar in 1969. That being said, I don’t believe in letting the truth stop a great story.

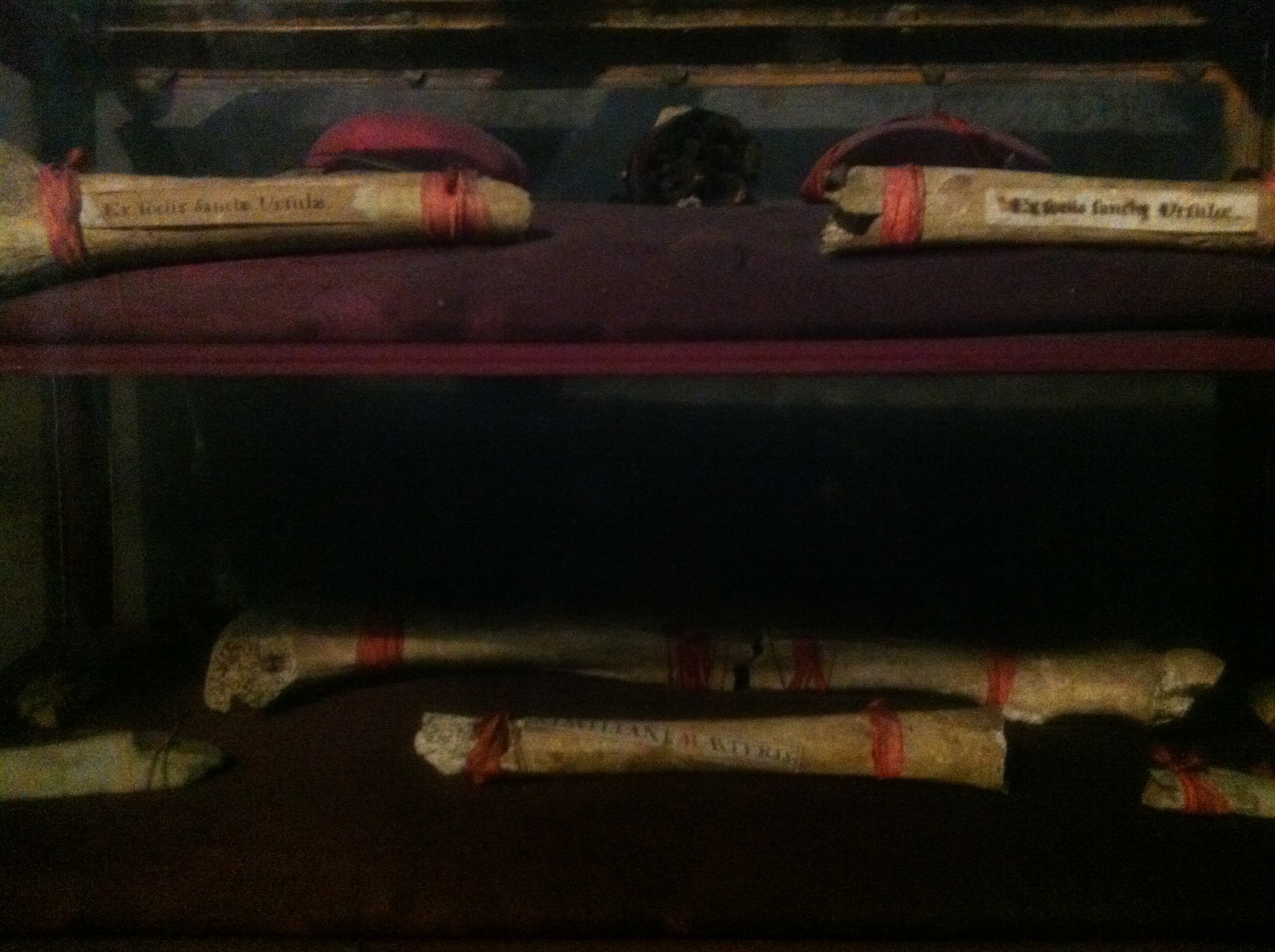

For me, the story starts in a dim chapel in the church of Saint-Severin in Paris where you can find a glass box containing a number of bones wrapped in red ribbon. They’re labeled “ex sociis santa ursulae”, meaning “from the allies of Saint Ursula”.

Saint Ursula as we know her probably originated from a 9th century sermon, which documented and expanded unsupported local lore about a Romano-British princess who died around 383. She was betrothed to a pagan prince but before she would marry she stipulated that she must take a 3-year tour of European holy sites, including a pilgrimage to Rome with 5 or 8 or 11 virginal ladies-in-waiting. At the end of this tour, she landed in Cologne where the Huns martyred her and her entourage.

There are dozens of variants on this basic story that alter where she was from, where she went, and whom she was with. Sometimes they include miraculous details like crossing seas in one day, visions of martyrdom, and angel-sherpas in the Alps. However, no record of Ursula, nor the pope they say she visited in Rome can be supported by historians- even those of the time like St. Gregory of Tours, who certainly had no objections to including some credulous accounts of miracles in his histories.

The most noticeable variation in the story dates back to 922 when the 11 virgins became 11,000. The Bishop of Cologne mistranslated (or perhaps zealously embellished) the Latin abbreviation “XI. M.V.” into “undecim millia virgines” (11,000 virgins) instead of “undecim martyres virgines” (11 virgin-martyrs). But it improved the story and it stuck.

So they accidentally invented more martyrs than there were in the original story (which was probably invented anyway)… that’s interesting, if a little dry. Here’s the big twist: there are, according to church records, over 30 tons of human bones on display all over Europe that purport to be the remains of these virgins- like the ones in this box. In Cologne you can even visit the Golden Room in the Basilica of St. Ursula where bones line every wall and skulls are kept in golden reliquaries. Local lore has even adapted over the years to explain why the bones of men and children have turned up here (though in 1835 a surgeon had to leave town after suggesting there might be a few mastiff bones too). Clearly they don’t believe in letting the truth stop a great story either.

But while we’re on the topic of huge bone collections and surgeons, step outside of Saint-Severin into the courtyard and see a little bit of obscure Parisian history. The arcaded gallery is what remains of a charnier, and the courtyard is a former mass grave. It’s no longer in use. Due to wars and epidemics (sometimes caused by cemetery over-crowding itself), Paris has an odd history of relocating the dead. But here, in the 15th through 18th centuries the wealthy were buried in the private niches and as the mass grave overflowed, bones were moved into the hollow spaces inside the walls of the charnier. That’s actually the primary difference between a charnier and a charnel house. A charnel house is intended to accommodate a large number of bones while a charnier includes space for private tombs and epitaphs, as well as some additional bone storage. As for its relevance to surgery, in 1474 the first gallstone operation took place in the charnier on a prisoner condemned to death. King Louis XI offered him his freedom if he lived though the experimental procedure, and he did, but I bet he doubted the odds when they told him they were going to operate right in the graveyard.