The Mummies of Mexico City

Originally published on Atlas Obsura.

Being in Mexico City for Holy Week has its advantages. If you’re interested in Catholic rites and rituals you’ll find plenty to do during the solemn holy days leading up to Easter. Some parishes sponsor reenactments of the crucifixion performed with varying degrees of historical accuracy and gore. Others hold funeral processions featuring life-sized effigies of Jesus in glass caskets. In a handful of places you can still find people who burn Judas in the form of papier-mâché devils.

But if you’re interested in traditional tourism or just looking for something to do in between services, you’ll find you’re mostly out of luck. The historic churches are in full mourning. Their best artwork and altarpieces are obscured by purple drapes to emphasize the sadness of these holidays. Many of the city’s excellent museums are closed. The locals are going to church, getting out of town or just enjoying some time off. I was the odd tourist out — wandering around the city on a day when everyone else had somewhere to be.

That’s how I wound up alone with twelve mummies. Looking for something to do in between Holy Week solemnities, I went to one of the only museums open during the later, more sacred days of Holy Week — the Museo de El Carmen. The museum, which primarily features Colonial era religious art, is housed in the old monastery school of San Ángel. Although it seems strange that a religious museum would be open on the holiest days of the year, the reasons for that are as much a testament to its colonial past as its Spanish-style architecture and cobblestone streets.

The monastery school and attached chapel were founded back when San Ángel was a rural town, separate from the massive sprawl of Mexico City. It was designed by Spanish Carmelite friar, Fray Andrés de San Miguel, and built between 1615 and 1628. Like many religious orders, the Carmelites raised money by selling space in their crypt under the school with the understanding that after a few years, the bones would be collected and stored in an ossuary so the space could be resold.

In 1857, the monastery school secularized under the Reform Laws designed to chip away at the Catholic Church’s hegemony in Mexico. This ultimately led to the school being abandoned by 1861. At that time, the crypt was simply sealed up with its current set of dead parishioners inside.

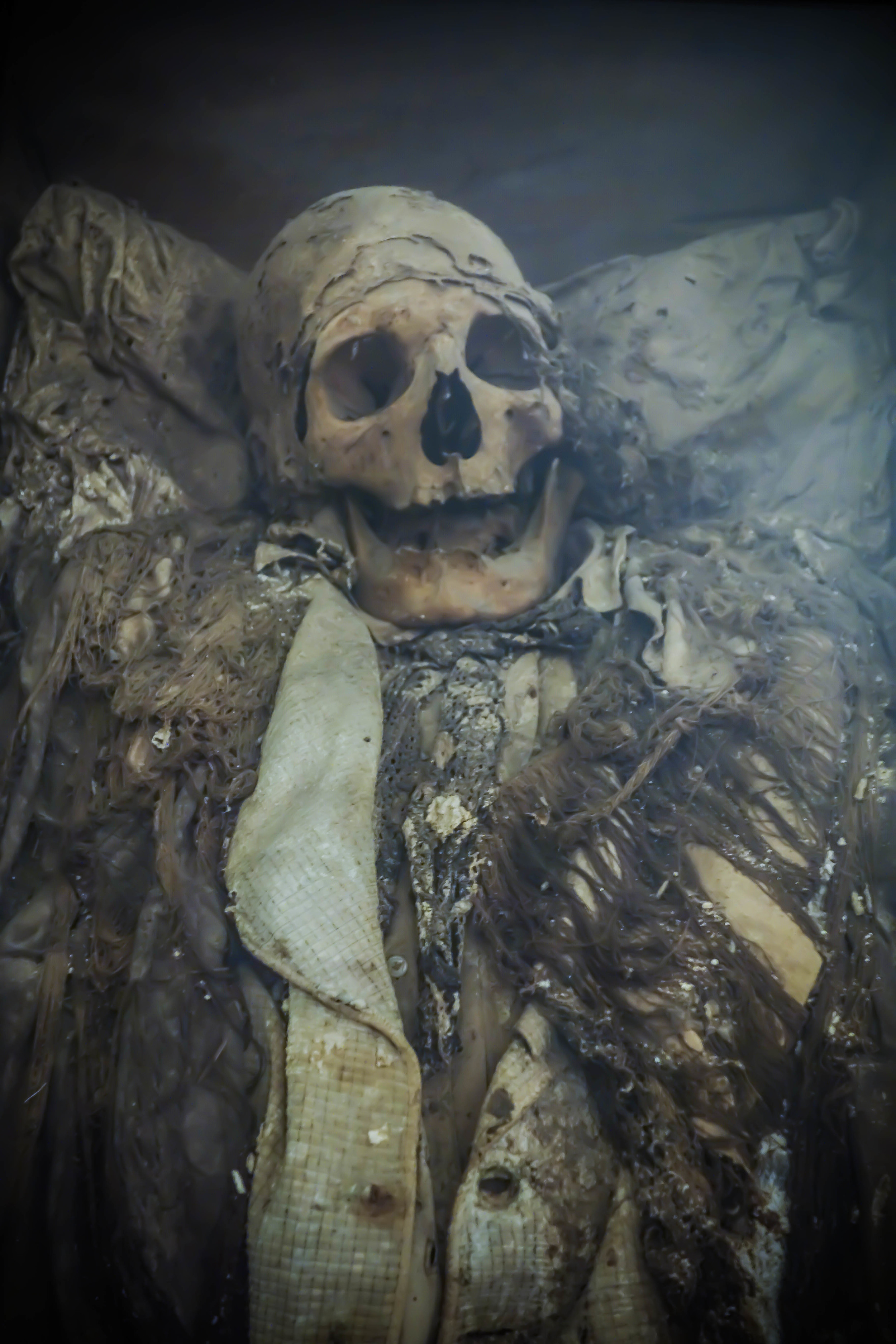

The crypt was forgotten about until 1917. That year, members of the Liberation Army of the South, a Revolutionary force dedicated to land redistribution for peasants and indigenous people, raided the monastery school. When they lifted the heavy cover off the crypt, they were surprised to find a cache of naturally mummified bodies instead of monastic wealth. The land in San Ángel was known for being ensconced in volcanic rock and the unique profile of this soil allowed many of the bodies to dehydrate quickly and discouraged the bacterial and fungal growth that would normally aid decomposition.

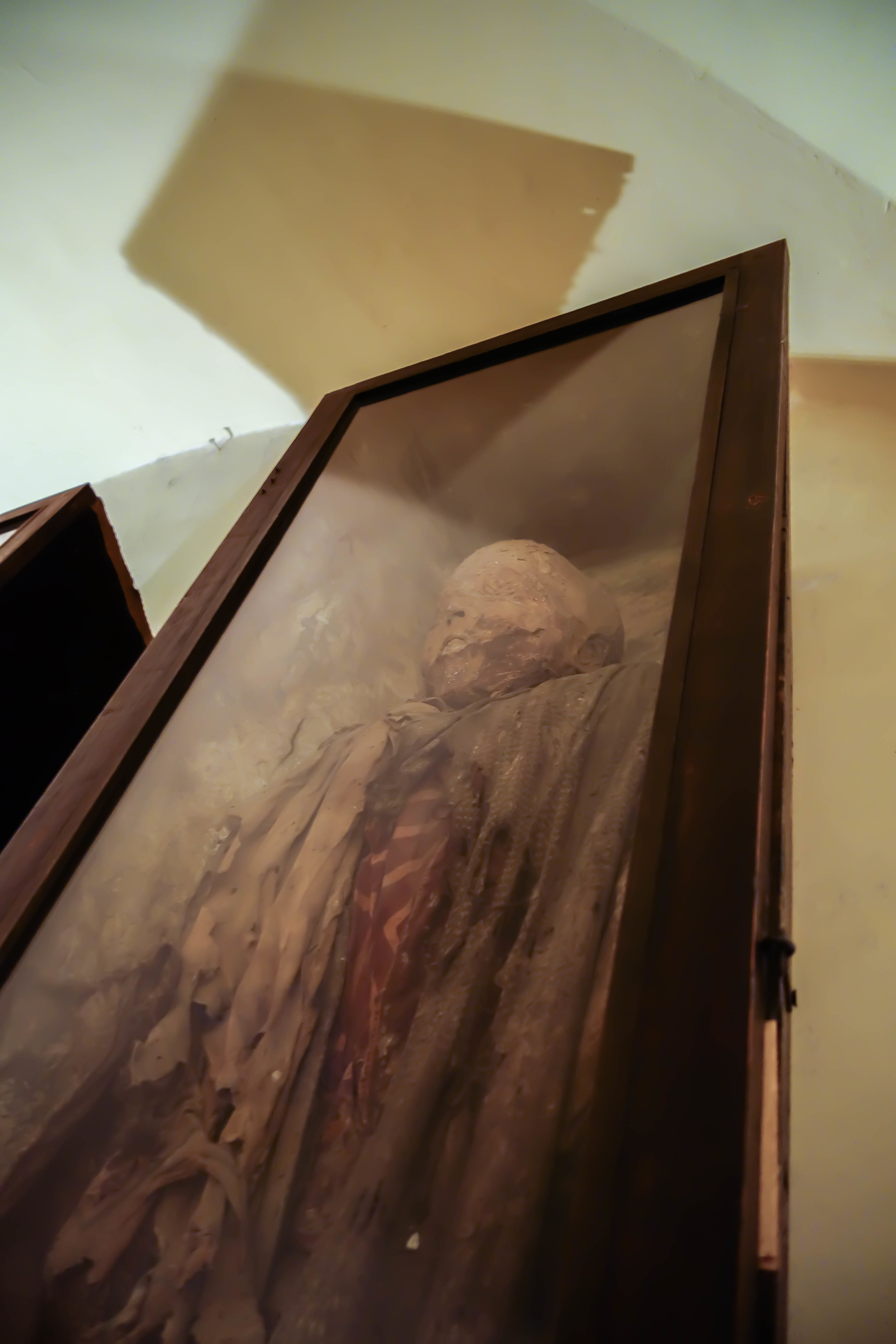

The soldiers left the mummies intact, but left the crypt uncovered. Within the next few years, the bodies were discovered yet again, this time by citizens of San Ángel secretly exploring the decrepit school. Word gradually got out and the mummies became well known around town. According to church lore, a Carmelite friar tried to convince the people of San Ángel to rebury the mummies but the town refused on the grounds that they had already adopted them as citizens. In 1929, the mummies were placed in their velvet-lined wood and glass caskets that are still in use today.

Though the chapel at El Carmen is still consecrated and owned by the Catholic Church, the monastery school and its crypt are still secular and have been run by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia since 1939, hence its unusual opening during Holy Week.

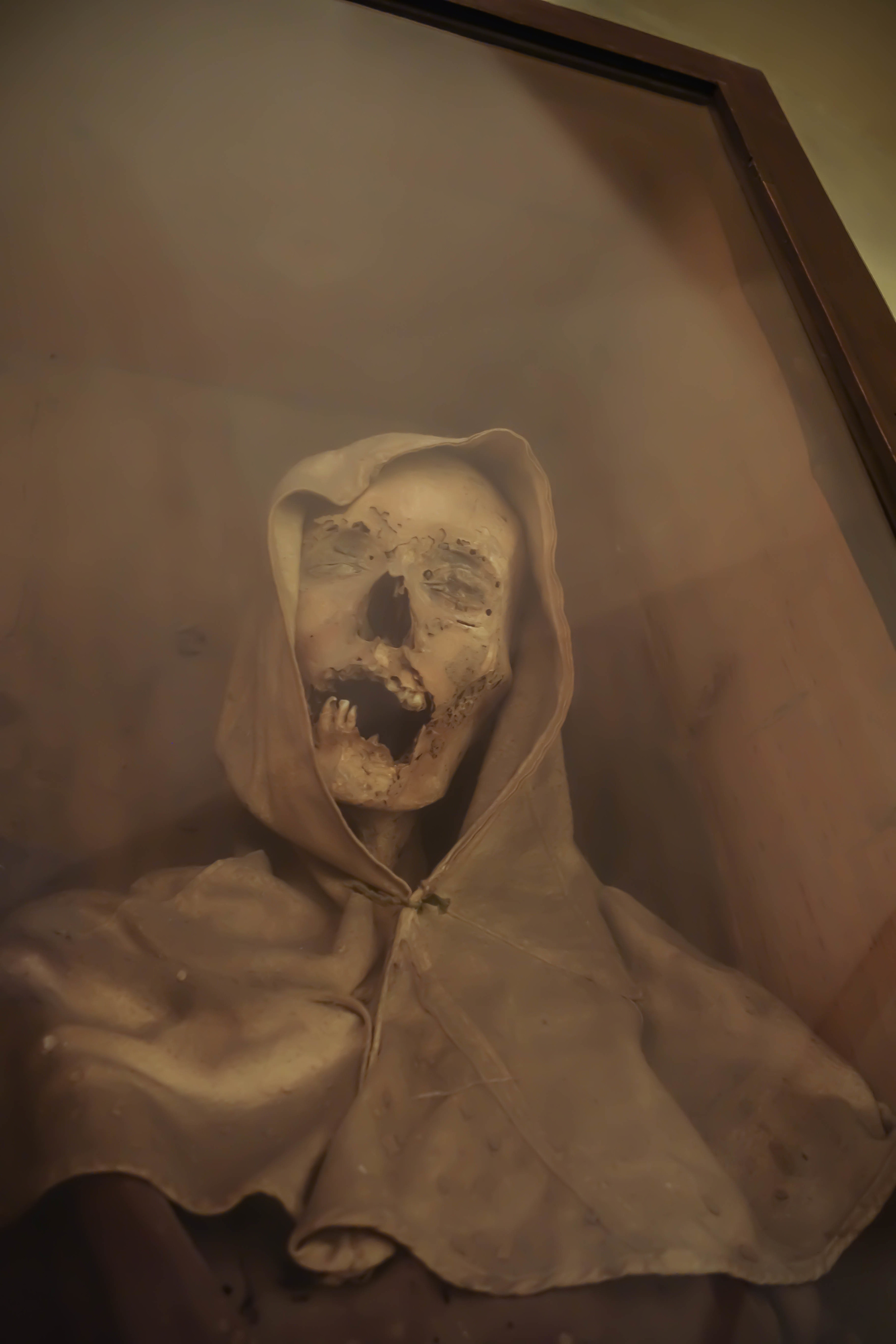

In 2012, the crypt was fully restored and opened to the public along side an exhibition featuring 30 large-format photographs of the mummies and a Day of the Dead altar that encouraged people, as cited in the Agencia EFE News Wire, to “contemplate these eminent people in detail: their expressions, the conditions of their skin, and the clothing with which they were dressed for death."

For those not scared off by their skeletal features, a closer look at the mummies allows a glimpse into their lives. In contrast to the more famous (and numerous) mummies of Guanajuato who were unceremoniously dug up for failing to pay a grave tax, these are clearly the bodies of well-to-do parishioners. They wear cravats, vests and jackets. One woman even wears a jaunty hat with a bow. Though dehydration has twisted their faces into grimaces, their bodies don’t show signs of trauma brought on by poverty and dangerous living conditions like those in Guanajuato do.

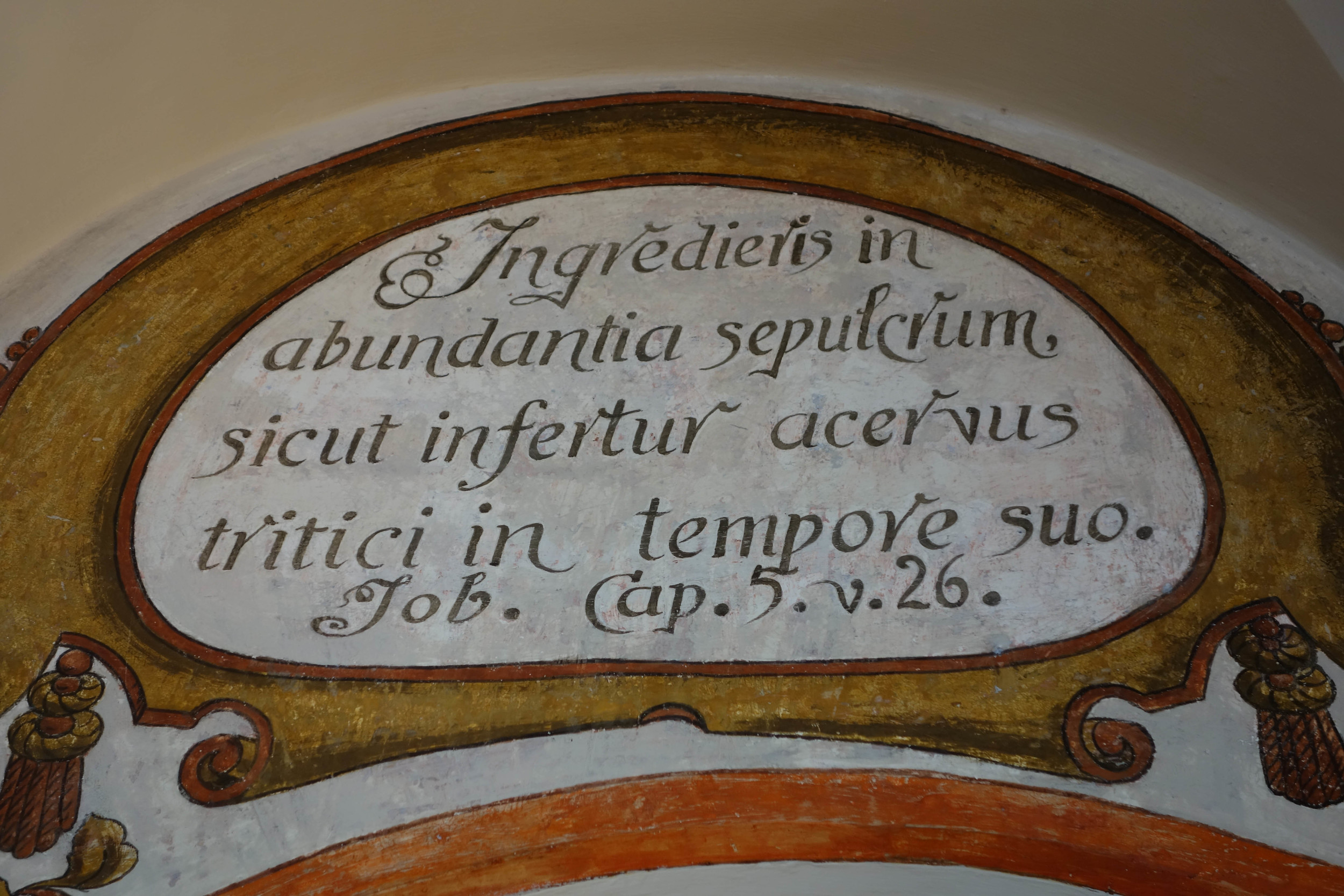

The inscription above the door to the crypt is from Job 5:26, appropriate for these comparatively serene mummies. “Thou shalt come to thy grave in a full age, like as a shock of corn cometh in in his season.”